Virgil Suárez was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1962. His artwork is featured in issue 40.1 of Interim.

Review By Carol Ciavonne

Her Scant State

Barbara Tomash. Apogee Press 2023

If, as has been said, Henry James’s late works can be compared to impressionist painting, then Barbara Tomash’s Her Scant State is, conceptually, much like the work of contemporary sculptor Rachel Whiteread. Whiteread’s resin, concrete and plaster casts of the negative space inside of doors, windows, rooms and buildings “show...something that is not, and can never be quite palpable” (Glover, Michael) and like Tomash’s experimental text “requires a constant reorientation of perception.” One of Whiteread’s first pieces, “House,” for which she received both the Turner Prize and the “K Foundation art award for the worst British artist,” (Walker, John) was a concrete cast of the interior of a soon-to-be-demolished Victorian building. Although the piece was demolished along with the building, the idea of an interior negative space made exterior, like a secret exposed, was a new departure in art.

Tomash, too, takes Henry James’s essentially Victorian house and makes us see it anew. Taking as her text Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, and in particular, his character Isabel (“I had doubts and Isabel” says Tomash) the living (and invisible) negative space where we think, speak and breathe is enclosed in form, but imagined to freely move… Isabel herself moves within and beyond the time period and becomes contemporary. And, through the device of upper and lower divisions of each page, as well as the arrangement of white space on the page, there is also allowance for what Whiteread has called: “...not…a space to be filled, but…an absence to be acknowledged.” Readers have acknowledged the literal absence of Isabel’s emotional side in James’s novel (New Statesman) but the subtractive process of erasure adds emotional depth to the “absence” of James’s Isabel. In Tomash’s brilliant visioning, erasure becomes a construction, not just of an absence, but of an inverse and vast intellectual and emotional space.

The Portrait of a Lady was written in 1881 and was an immediate success. It tells the story of a young and independent American girl visiting in England who comes into wealth via a generous cousin (also American). Having come away from her country to explore freedom and partially to escape a suitor who she fears might damage her independence, Isabel’s desire is to do good, or at least as she says, to have the choice to do good. But through the machinations of yet another American expatriate, she ends up married, not to the struggling artist and sensitive person she was hoping to help, but to the shallow and rather cruel man he shows himself to be. As well as being a “portrait” of a young and idealistic woman, James’s Isabel as a character explores the place of woman, the idea of freedom for a woman, and its very real limitations.

Whether or not one is familiar with James’s work, or this book in particular, Her Scant State and the emotions and questions it evokes are very much contemporary. Even the cover of the book, “The Fragment of a Queen’s Face,” (from a sculpture ca. 1390-1336 B.C.) hints both that the form inside will be experimental, broken or fragmented (as an erasure will be) and that the concerns of women it addresses extend both backwards and forwards in time.

As introduction, Tomash has begun with “Note” (an erasure of “Note on the Text” in the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel) and “Face” (taken from James’s 1908 preface to his New York Edition ) plus a delightful epigraph which hints at her philosophical and structural approach to Her Scant State: “As far as the limits of the room allow, I have asked permission, with a piano and with flowers, with phrases and gradations in speech, for a lapse in continuity.”

Tomash also gives a clear picture of her process/structure in the Source Notes at the end of the book: “Her Scant State is an erasure of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady. I kept strictly to word order but allowed myself free rein with punctuation and form on the page. The first half of the novel runs across the top of each page of Her Scant State. The second half of the novel runs across the bottom of each page.” The design of the book can work as a read-through of the first half or the second half, alone, but also works as a top-to-bottom reading of each page. The interplay between top and bottom also permits a fascinating contrast to, or alternatively, a corroboration of the reading above. Because of this generous arrangement, I have sometimes chosen to cite only one half of the text on a page.

Given that The Portrait of a Lady is the base for Tomash’s book, what does “Her Scant State” refer to? Certainly not a correspondence to James’s dense and detailed descriptions of clothing, rooms, buildings, landscapes and physical attributes, which by no means fit the definition of the word “scant." Part of the charm of his writing lies in his elaborate detail and description. “Dogskin gloves” and “brown velvet jacket” for example, are for the modern reader, evocative of time period, class and wealth. Tomash selects certain of these descriptions, but as with Whiteread’s works, there is a “reorientation of perception” in which we find ourselves in both the past and the present as if in a flickering light, candle to LED and back. The omniscient narrator in James’s work may see the characters’ blind spots but he does not and cannot capture the nuances of thought, almost proto-thought, of a human being. Rather than an imposed narrative, the ephemerality of thought in the fragmented selection of text and the feeling that is engendered from these fragments, are the basis of Tomash’s poetic project. Shifts in perception occur as the iteration of the process of thought itself as the reader moves from one persona to another, one reading to another, and the poetry of this is both diaphanous and powerful. Although “scant,” in this case the text itself, or the actual physical space left bare on the page, communicates a mental and emotional “state,” the “scant” erasure imagines a larger (more open) interior; an “absence” that allows “absence” and silence, pause and imagination.

Tomash’s story ( as opposed to the novel) is “scant” and the reader must interpret—as Isabel, or herself or Everywoman—(I have chosen to read as all three, yet it seems not a choice so much as a natural way of reading the text). It’s also possible to think of her “scant” state as being a state of mind not completely realized, or limited in some way, as surely Isabel is limited, at first by her own youth and ideals, and then by the manipulations of others.

James’s portrait centers very much on the theme of marriage; its great importance in Victorian society as a marker of wealth and class, as well as its limitations, particularly for women, a damned if you do and damned if you don’t situation, but particularly damned if you don’t. Here Tomash brings her response to the institution of marriage and its “scant state”; if we take scant to mean the opposite of full or complete, expectations unfulfilled, generosity taken for granted, small cruelties of withholding, or the fear of being subsumed. In James’s book, the marriages are all precarious; all are marked by loss; there is “no perfect little pearl of letting go” but more a case of “made her drop her biography.” Tomash’s Isabel acknowledges these feelings.

In Tomash’s writing, the scant state continues even to the intimation of abuse; emotional certainly, and though not mentioned directly in James, implied physical abuse that unfortunately transcends time periods.

Isabel’s marriage is not the only scant state in Tomash’s evocative book. Henry James was preoccupied by the idea of being an American. The country was barely a hundred years old when he began writing, and he, along with others, seemed to believe that certain nations had certain characteristics. Perhaps almost as a point of pride, James seems to endow Americans with generosity, as seen in both Isabel and her cousin Ralph, for example. But many of the characters in The Portrait of a Lady contain American “types”. A quote by Madame Merle (an American, and one of the more unsavory characters) gives a brief metonym of another supposedly American trait: “the breezy freedom of the stars and stripes” (184 TPL). Tomash, too, selects the word “American” from her source, but her text implies a much less favorable perception, reflecting our own time in which we have come to a dismaying, if not horrifying, realization of a quite different meaning to the word.

In contrast with James’s ideal of America, class, wealth, and property appear as in The Portrait of a Lady, but in a more inflected version in Her Scant State. We recognize that many Americans have been raised in what in other times and in other places (and is still true today) is considered great wealth, to the detriment of most people in the world. In Her Scant State, a politically awakened and modernized Isabel takes notice.

Isabel’s considerations, angry and ironic (in Tomash’s book) are our own considerations. In our America, a scant “state” exists, with meager consideration for the poor, the oppressed, the mentally and physically ill.

There is much to touch us in Her Scant State, but another beauty of the book is that the experimental structure allows us also to read some of the work as a poet’s notes on poetry. Here, the poet herself becomes a persona. While it can be surmised that James as author is very much manipulating the writing of the story itself (this is the definition of a novel isn’t it?) and the narrator in The Portrait of a Lady allows his own thoughts to be discerned from time to time, in complement and contrast Tomash writes beautifully lyrical poetry, never more so than in this poet’s manifesto:

And in another poem that can also be read as a subtle commentary on writing, the wit of the division of syllables both calls to mind the measure of a waltz, and satirizes that romantic vision. The word “romantic” is broken and “nothing could exceed/this perfect”— the poet herself, perhaps, saying “Putting a thing into word pictures an essential need.” But there is also the necessity for “…so many pretty banishments.”

************************************************************************

In The Portrait of a Lady, Isabel shows her intention, and James gives us a hint of her downfall, in the following passage :

“ I shall always tell you” her aunt answered, “whenever I see you taking too much liberty.”

“Pray do; but I don’t say I shall always think your remonstrance just.”

“Very likely not. You are too fond of your liberty.”

“Yes, I think I am very fond of it. But I always want to know the things one shouldn’t do.”

“So as to do them?” asked her aunt.

“So as to choose,” said Isabel.

(70 TPL)

This passage is significant to both the process and the content of Her Scant State. In James’s novel, Isabel’s “choices” are not hers, although she thinks they are until almost the end of the book. Isabel is weighed down by her stubbornness and her youth, as well as her idealism, so that at almost every step the reader is imploring her to consider and to be truthful with herself, to let herself feel what she feels instead of directing her life. There is also the weight of inherited wealth within the story, the weight of being American (and the expectation of how Americans should resemble America) . This is the intended weight of James’s story but there is also the unintended, as Isabel is manipulated both by the story line and by James as author and male in the time in which he lived. In Her Scant State, we see and we are a different Isabel. Scattered through Her Scant State are the possibilities for her and for us, the openings for the “choices” for Isabel/woman that are not possible in James. This Isabel, in Tomash’s new language, thinks and feels differently, expansively. This is both a function of the erasure itself, and the process Tomash has set for herself, as well as the respect and love Tomash has for both author and character. It’s like arguing with a mentor, but in a beautiful and complex language forever unknown to them, and inconceivable.

Tomash has employed James’s novel as a plinth, a translucent one (like Rachel Whiteread’s “Monument”) that creates the support for a new and poetic response: an airy structure that lets in the sky and its weathers, with the absences of loss and betrayal acknowledged through time. The hope that may or may not be predicated in the end of The Portrait of a Lady is, in Tomash, very present. Isabel, you, I, have a sense of being able to speak our thoughts and emotions, and to feel them honestly in ourselves. The writing itself lets in air. The sense of possibility is voluminous.

Works:

Henry James. Wikipedia. 8 May 23 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James

James, Henry. The Portrait of a Lady. Penguin Classics. Ed. Intro and notes Phillip Horne. 2011

Appendix II: Henry James’s Preface to the New York Edition of The Portrait of a Lady. (1908).

Cohen, Alina.”Rachel Whiteread’s “House” was Unlivable, Controversial and Unforgettable.” Artsy. Sept. 24 2018 https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rachel-whitereads-house-unlivable-controversial-unforgettable

Glover, Michael. “Rachel Whiteread’s White Blight.” Hyperallergic. May 15, 2021. Hyperallergic.com

Rachel Whiteread. Luhring Augustine Gallery. luhringaugustine.com/art https://www.luhringaugustine.com/artists/rachel-whiteread#tab:thumbnails “a constant reorientation of perception.”

Rachel Whiteread. Untitled Monument. Commissioned by Cass Sculpture Foundation; displayed on the Fourth Plinth, 2001. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/monument-310254

Rachel Whiteread. Wikipedia. Denny, Ned. New Statesman. 9 July 2001 "It's a simple trick, but an effective one, and the associations it conjures – heaviness and lightness, earth and heaven, death and life – are thought-provoking and manifold [...] Whiteread's Monument, as light and gleaming as the plinth is dark and squat, is the only one of the four commissioned pieces to allude directly to the plinth's defining emptiness. She sees it not as a space to be filled, but as an absence to be acknowledged, and she does it well."

Rachel Whiteread. Wikipedia. Walker, John A. (1999) The house that no longer was a home, excerpt from Art and Outrage. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rachel_Whiteread#cite_note-25

Tomash, Barbara. Her Scant State. Apogee Press 2023.

Wilson, John. Interview with Rachel Whiteread. This Cultural Life podcast. Sounds BBC. Released 04 Feb 2023 https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001hws2

Carol Ciavonne’s poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Boston Review, Colorado Review, Interim, and New American Writing, among other journals. Essays and reviews can be found in Interim, Colorado Review, Rain Taxi, Entropy, and Pleiades. She is the author of Birdhouse Dialogues (LaFi 2013) (with artist Susana Amundaraín) and a collection, Azimuth (Jaded Ibis Press 2014). Ciavonne is an editor of the online journal Posit.

(30, bottom)

(33, full page)

(28, full page)

(30, top)

(25, top)

(58, full page)

(51, full page)

(34, full page)

Review By Brigette Lewis

Television, a memoir

by Karen Brennan. Four Way Books, March 2022.

Many Lives, Many Selves: a review of Karen Brennan's Television, a memoir

The word “television” has meant different things at different times. For example, in my particular household when I was a kid in the 1980s, the word “television” did not mean “cable.” It did not mean “MTV” or “VH1” like I wished it did. It did mean having to stand up and walk to the physical television—a giant beast of a thing with a depth of probably two feet—to manually turn knobs and press buttons. This is how channels were changed. This is how the volume was adjusted. It is something of an art, turning the volume up or down when one’s ear is so close to the speaker because one is turning it up or down for when one's ears are back on the couch.

In Karen Brennan’s Television, a memoir, the word “television” means many things over the course of the book. In earlier essays, it means “Mama,” a show that ran for most of the 1950s. It means “Lawrence Welk” as well as “Mad Men” and “Big Little Lies.” It means gathering en masse at the home of the neighbor who was first on the street to get a TV. It means being interviewed in front of the camera as a teenager—“princess” of Luxembourg for the International Azalea Festival—in the lobby of the Sheraton Hotel. It means binge-watching. It means not having a TV in the house on principle. It means your father buying one for you anyway and you standing silent and seething while your children cheer.

No matter your age now, no matter what the word “television” has or has not meant for you, for each and all of across time us it means the transmission of moving images and sound. It means light blaring behind screen to flicker the impression of life before our very lives.

There are seventy-six essays in Brennan’s memoir. Seventy-six fragments, episodes, channels. Seventy-six full color visions that move and breathe in the imagination suspended. A lifetime in scenes. Excerpts of moments that represent larger stories. Mundanity. Reflection. Heartbreak and devastation play out next to sweetness and surprise. Drama and comedy, and at times the hybrid dramedy, but absolutely no after-school specials. Brennan looks keenly and with curiosity. When writing about her life, especially the most difficult parts, she honors events with honesty and emotion, and by not trying to sum them up neatly. Open endings abound in these seventy-six flash essays. Uncertainty is embraced almost as a matter of identity.

I wasn’t interested in my appearance and when I looked in the mirror, I felt that the face I beheld was not my own. Why this face and no other? I remember wondering. In place of thinking, I dwelled in wondering—not bafflement exactly, but surprise that this or that would be such and such a way, combined with a kind of anxious curiosity. I hoped all things would be revealed to me, sooner or later (Brennan, 8).

Lately, I have been thinking much about the phrase “everything happens for a reason.” My belief is that it does not. My belief is that humans are wired for story and that this narrative drive allows us to make retroactive sense of our lives, sense that we might then see—not as something we participated in, but—as something entirely outside ourselves. One of my favorite things about Television, a memoir, is Brennan’s innate ability to not look for reason. True, there are times her writing leans toward the philosophical or pondering:

From a neighbor’s house, the happy strains of a party and once again we are outsiders. There is laugher, music, the lilt of easy conversation between adults of goodwill, people who actually like each other. Our own life, by comparison, is lackluster, dull, often complicated and frustrating. Our relationships are fraught with difficulties, too often lacking in ease and warmth. We are lonely, plagued with loneliness, suffocated by solitude. No wonder our presence is not required at such a gathering. But were we to peek through the picture window of the party house, we would find no lively human guests, but a flat screen teeming with beautiful, animated simulacra and person asleep on the couch (Brennan, 105).

And is this not a most relatable of paragraphs? There are studies that link elevated screen time—a phrase that used to refer solely to television, but now has come to encapsulate computer usage, social media, smart phones—with depression and anxiety. We’ve all seen the news that Meta/Facebook is aware of the deleterious effect of Instagram on teenage girls. Like any screen ignited with interiority that is ultimately absent, television can connect and inform—and it can also make us very aware that the place where our bodies exist in time and space can run with sudden coldness in comparison to that which is lit from within.

The author twice references Madame Bovary, a book about a protagonist of the same name who is known for having a somewhat foolish mentality, of being wont to wander among romantic daydreams rather than live with her feet on the ground of Normandy. Speaking of her childhood self, noting her “difficult personality” and lack of self-awareness, Brennan wonders if reading Flaubert’s novel at this time would have caused her to recoil “from [her] own vanity and superficiality (57).” Instead, she read the book as an adult when living in Puerto Rico. “Invited to observe the Puerto Rican Parrot with Nathan Leopold, a man newly sprung from a life sentence for the murder of a fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks,” the author wants nothing to do with the man and instead stays home and reads Madame Bovary which is to say: are we all not in the starring role of our intense, albeit mundane, dramas?

Except Karen Brennan does not strike me as she purportedly sees herself, with a “shallow, self-serving side.” I believe her when she says this side existed or sometimes exists and understand how it would come to be so, a child living in a home fraught with generational wealth and expectations, a mother changed by polio. a father who deems her worth relative to her ability to reproduce. If television—screens generally—have the possibility to render the viewer feeling like a foreign object, this memoir of that name does the opposite. Brennan’s visits with her life’s experiences (and she has lived, it seemed, many lives, many selves) are expertly crafted, written from the perspective of the present looking at the distant and not-so-distant past, sans nostalgia at that. She lets the many former versions of herself, glamorous and positively not so, pixelate and take shape. She presents things for view. Then she changes the channel to another scene.

When I finish reading Television, a memoir for the second time, I play Lucy Dacus’ Home Video album. From the first track “Hot & Heavy:”

Being back here makes me hot in the face

Hot blood in my pulsing veins

Heavy memories weighing on my brain

Hot and heavy in the basement of your parents' place

Brennan returns “hot in the face, hot blood in [her] pulsing veins” to feel what she felt in moments of great anguish, sorrow, anger, boredom even. She lets the images take shape. She creates transmissions of them—all light-flicker and wonder—for us. She turns up the volume.

She [flies] back to those lost years and they cannot contain me. I am mid-flight, inventing a fairy tale, while around me the world falls apart. The table is set so carefully, forks on the left side, knives and spoons on the right, while not so far away someone is in handcuffs and someone else is weeping uncontrollably (100).

And she does so—“heavy memories weighing on [her] brain—so that we may come along. No, it is true that I have never found myself in a restroom with Marlene Dietrich. I have never had to visit my daughter in her long-term care facility for patients with traumatic brain injuries. I have never been fired under the pretense that I wore funny hats to work. But, also, haven’t I?

Brigitte Lewis is the author of Origin Stories, winner of the Iron Horse Literary Review Chapbook Prize, 2020, and the memoir Speculative Histories, forthcoming from JackLeg Press, 2023

Preface by Claudia Keelan

Introduction by Andrew Nicholson

Hannah Dierdorff

Winner of 2022 Betsy Joiner Flanagan Award in Poetry for her book Rain, Wind, Thunder, Fire, Daughter

Wood | Word

Ponderosa: the jigsaw pillars that invoke

a spiritual feeling, pillars evolved to survive

surface fires, their lower limbs dropped with age.

Ponderosa: the name a Scottish botanist gives

the pine while botanizing along the Spokane

River in 1826. Ponderosa: in Latin, heavy,

weighty, significant. The Latin name became—

unusually among trees—the common name. Ponder-

osa: the tree of many names: long-leafed

pine, pumpkin, yellowbelly, bull pine, black-

jack, red pine, silver pine, pino real (true

pine). Ponderosa: ponderous: meditative,

labored, profound, slow because of great weight,

like a book pinning the pen in place.

Psalm Sleeping Between Circles & Lines

And God separated the light from the darkness.

Genesis 1:4

How God’s name divides (the wicked |

the righteous) the way my father and I

build a fence to keep the neighbor’s knapweed

from our garden. To build a fireline, cut

and scrape vegetation till you reach mineral

soil, a strip wide enough to stop embers

from blowing across like seeds hungry to root

and feed. Eventually the firefighters

do prevail. Do encircle. Do contain. The edge

then felt with bare hands to find what heat

remains. Let no fire escape.

For a fire escape,

he hides a ladder under my bed | over the bed

a boy spreads paper hearts, red as the letters

I write then burn out the window.

Sonnet with a Mouth Full of Dollar Bills

Economy: the production and consumption of goods

and services and the supply of money as in “Ponderosa

pine fuel[s] the economies of the West beginning

in the 1860s.” Economy: the proper management

of the body, diet, regimen (obsolete). At thirteen,

I exchange spaghetti for celery, cereal for the belly’s

bright ache. Economy: a sparing or careful use.

Railroads induce clearcutting. I dream of cutting

flesh from bones, pelvis, femur, clavicle, rib cage,

breasts and sex erased as the red numbers blink

down: 130 to 108. Economy: relating to the inter-

dependence of living things. How the mothers praise

my body—straight, pale, and clean as the logs

laid at the lumber mill north of Coeur d’Alene.

Sonnet Starting with Arson

August 2015. When the smoke settles

in the city like sediment in a stream, my mother

buys masks, forbids us from opening windows,

the heat climbing through the old house to breed

in the attic where I sleep. An hour away

near Fruitland, a man dies trying to save his farm.

The ceiling drops, the sky so close I reach up

and choke God with one hand. Thus men are held

in the hand of God over the pit of hell... the fire

in their own hearts struggling to break out. The Forest

Service documents the success of Initial Attack

containing fires in Washington and Oregon. I

document the color of the sun cutting through

the haze, its eye unblinking, red as fish eggs.

Forty miles south of my parents’ house, a wildfire decimates the small town of

Malden and consumes thousands of acres of wheat

becoming witness

was not

enough

outside the ash-filled foundation of what was once

i’ve seen loss i’ve

corkscrewed

split

off

This wildfire season has been

the signals of climate change

the future

a blackened brick shell

nearby

i wish i

returned

why

save

I

fire

spells end spells beginning

space creates

others

Hannah Dierdorff is a poet from the scablands and pine savannas of Washington, the unceded ancestral land of the interior Salish people. Most recently, she's lived with her occasionally feral black cat in Virginia where she received her MFA from the University of Virginia and worked with the Appalachian Conservation Corps. She is the recipient of the 2022 Dogwood Literary Award for poetry, the 2022 Daniel Pink Memorial Poetry Prize, and a Vermont Studio Center Fellowship. Her writing has appeared in journals such as Cut Bank, Arkansas International, About Place,

and Willow Springs.

Bruce Bond

Winner of the 2022 Test Site Poetry Series for his book The Dove of the Morning News

Imperium

When I was small, I drew small people and gave to each the life

of the others, the sense of a solitary shared self that many make,

when gods above them flip the pages. I was learning how to think

of others when they are far away, to lay down a sketchpad of faces

in incremental variations, the closer the semblance of the moments

the stronger the illusion, the more fluid the movement of the lips.

And once, when I was small, a mother stepped out of the paper,

out of the steady brokenness that gives to each a silent language.

*

I was learning how to think of the self, not the self as the river I am

when I have yet to say river or self or I am learning how to think.

Not that kind but the chatter of a film projector, where I play a role,

a figure in an animated feature spooling in the basement of a brain.

The river you hear is no river, but the crackle of an old soundtrack.

Its crawl of fiction crumples as it turns. But the ache of light is real,

the way it suffers to be seen, heard, taken over. I think therefore I

fail the surplus of experience. The dark of whom is everything I love.

*

A child crawls in a hall with a mirror at the far end, and as the figure

in the mirror crawls a little closer, the child feels a little larger, darker.

With every move the child makes, so too the stranger whose shadow

trails into the hall in the mirror. If a shadow could stand, it would be

a monster. It would be a child who cries in pitches only dogs can hear.

And shiny objects with hearts of glass. And when the mirror shatters,

a monster would rise from the shards to see in them his brokenness.

He would kneel down like mist at dawn to give to each a child’s name.

*

Long ago, a flock of blackbirds flew into one man’s ear and turned

into a solitary figure. Blackbird, he whispered, and the bird flew away.

Just when he thought himself one of the family, he found his life

abandoned. When at last he woke, one of his eyes was gouged out.

Bird, he said, more bitterly this time. With every thought of the wound,

how it ate into the visual world, he saw the glossy jacket of the bird.

With every song, his blood turned cold. And when he woke again,

lo, his eye returned, but everything he dreamed was bitter and black.

*

Begin with a four-year-old who spins a dial, and the needle falls

on orange or green. Then a gift, a shirt in the corresponding color.

Now ask the child to read cartoon figures in the same two shades,

unscripted scenes whose silence summons the prejudice of being

one of the fold. That sideways glance. Is it conspiratorial or shy.

A shirt will tell you. Truth loves no one. But dread has favorites.

Its games are cruel. Its brain is a child inside a brain that watches.

Like a wilderness some call bankable or pointless. Others, home.

*

I met a squirrel who came to my window every morning to be fed,

and though I was never sure it was the same squirrel, I called him

squirrel and loved him all the same. Him and his schizophrenic

freeze-tag with voices in his head. The squirrel brain in me said,

Maybe you just love the love of squirrels, and it was true. My email

signature read, yada, yada, PhD, lover of squirrels. My motto was,

The good of the relation is something other than the good within it

A squirrel told me that.Take this, I said, a nut. Whoever you are.

*

Frankenstein the creature will tell you, the volt that shocks the dead

to life falls from clouds whose rage drifts in from the unseen story,

like a mob in the making, waiting to explode. He will tell you, he is

an animated figure, a lightning rod, a doll. Heaven strikes the nerve

of what the frightened call a monster, and his eyes in ours are ours

through which we see his father turn away. It will take a blind man

to read the stapled lesions in a startled face. The proximity of touch

will tell you. Forget what you heard. To relate belongs to one alone.

*

In Bagdad once, a Mongol herd rounded up the priests and scholars,

cut their throats, and hurled them in the Tigris. It turned the water

to rust, the widows to water, eyes downstream to the littered shore.

Then to make a bridge, the invaders dumped wagonloads of books

that stained the current black. When a violence spreads, it scatters

the remnants of erasure. It flows into gutters, trickles under homes.

scours faces of their features, out there, where the story ends and ends.

Above earth and below. The river affirms the terms of its surrender.

*

It’s alive, says the scientist whose unkempt hair stiffens into quills,

which tells you something is seriously wrong below, inside that head,

his pride afloat the danger music of his blood. It, the scientist says,

but what do we call the new human whose parts are old and aching.

If not Lamp of Knowledge, what. Mania, Regret, No Son of Mine.

No. The affair began with a fiction, but suffering is another matter,

and love needs a name. It needs a threshold, the way a hand needs

a shadow hand to lie down on, to press against the shadow of a face.

*

If you draw enough and talk and, in your talking, listen, you begin to light

the many apartments of a project on the margin. I too am worried, scared,

beaten by strangers I later punish in my dreams. I see in each the avatar

I cannot be, no stranger can, no tribe, no urchin who thinks in exaltations

of violence and cartoon. If, in some feature set inside a neighbor’s kitchen,

you dab her open wound with a cloth, you understand, as lesions must,

the primacy of touch, that place the tremor of the lidded eye subsides.

But you are in there still. Like a thousand dark apartments. Like blood.

*

The face of many is one face, its eyes sewn shut. Its mouth gagged.

Its suffering a string that gathers followers like crystals. I have seen it.

I have given the breath of a creature to whom the many are a stranger.

For though the face is blind, I see, in it, a mirror, the kind that calls

from the end of a long dark hall. Lonely as a monster or some such friend.

What I do not, cannot, know fills the pitchers of the grieved with blood.

And those who hang in the bayou break down into particles, frames, flies.

All night, they bronze the wind, they toll, waiting for the one to cut them down.

Bruce Bond is the author of thirty-two books including, most recently, Plurality and the Poetics of Self (Palgrave, 2019), Words Written Against the Walls of the City (LSU, 2019), Scar (Etruscan, 2020), Behemoth (New Criterion Prize, Criterion Books, 2021), The Calling (Parlor, 2021), Patmos (Juniper Prize, UMass, 2021), and Liberation of Dissonance (Nicholas Shaffner Award for Literature in Music, Schaffner Press, 2022). Forthcoming books include Invention of the Wilderness (LSU), Choreomania (Madhat), Therapon (co-authored with Dan Beachy-Quick, Tupelo), The Mirror, the Patch, the Telescope (co-authored with David Keplinger, MadHat), and Vault (Richard Snyder Prize, Ashland). His work has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including seven editions of Best American Poetry.

Brandon Krieg

Change of Possession

1.

The trail led to rooftops

instead of sea,

a quail in a small pine by a tagged wall

gurgled plaintively

How Many Locals

Did You Fuck on Your Vacation?

2.

Lost, I punted

a pinecone over its parent pine

Sidereal Day

Sad me, completist of vales,

obsolescent

dial turner

until

hanks of Hank catch in barbed static

Foolgatherer

working the seeming discrete

into clusters

bee pollen → fireworks

sold in the same fairgrounds lot

a vendor hugging to adjust

his ridiculous

heap of peanuts

laughing like a lost love is still

slipping his embrace

All the years

of opening wider to sun and rain in one

wave-polished drift log

floated off as smoke

from last night’s bonfire

like this thought: was it

sparks or moths,

mere chance or chance-

as-god

constellationed

the coat-wool you wear I follow

to the sea-cliff through daybreak mist?

Don’t Waste Time Wishing the Machine

that slashes stalks would first

carefully unhook

cornflowers and morning glories

See if you can relax 10% more, 11% more

like a raptor counter waiting to tap an iPad

Oh, Endless Mountains Area!

(next six exits)

Park

at the overlook, then

overlook

Alarm Calls

I see through sequoias and madrones the new

lipstick-shaped skyscraper across the bay

that already sinks a foot each year, looming over

the cranes that inspired the 4-legged vehicular killing machines

in the old blockbuster. A sawed-in-half deadfall

pushed off the trail says GS + RT, a tag

inside the porta john says Shorty Pooped Here,

its plastic urinal tilted to pour a cascade on boots,

little mock waterfall in this land of everlasting

drought and fire. Poor little VCs

with your billions to lose, don’t worry,

this flyer advertises the services of Water Witches

who for a fee dowse with downed branches sites

for industrial pumps to try and suck up what isn’t there. Everything

is mock now, I must be

old because it doesn’t surprise or bother me

those cranes unload crates of batteries the future will go

dead without or with, with

Wall Street betting on it. Later,

on the terrace, I wonder

if hummingbirds only visit the hanging

feeder when no one’s here, and who looked at one closely enough

to inlay its shape on this guitar’s pickguard? Must have been a

dead one stuffed one specimen. Is it a grigio or gringo

haze tuning this afternoon so that the spider web

between the balcony railing and its strand of Christmas lights

in July billows overstaying seductively? I refuse

to burn the web’s unique concentric handiwork on my mind’s eye

after a friend told me the allegory of our times: he locked himself out

and, waiting for his landlord, concentrated his focus

on the song of the bird he was hearing, in order to recognize later

its noble invitation back to the present moment, but

found out it was common, invasive, constant

in the neighborhood, un-banishable to the background—

he wakes to it now through the wall, he

is ripped by it out of every reverie.

Brandon Krieg is the author most recently of Receiver (Herring Alley Pamphlets, 2021) and Magnifier (Center for Literary Publishing, 2019) winner of the 2019 Colorado Prize for Poetry chosen by Kazim Ali and a finalist for the 2022 ASLE Book Award in Environmental Creative Writing. He lives in Kutztown, PA, and teaches at Kutztown University.

Angie Estes

Relais du Silence

When someone dies

in the Limousin region of France, they say

Il a laissé son écuelle, He has left his bowl, so a small

bowl is filled with Holy Water into which

an evergreen branch is dipped to bless

the body. After burial, they place the bowl

at the head of the tombstone: it can never

be used for anything else. My friend Jacqueline

says that some people insist

on a hierarchy of sorrows. If your

dog died after twenty years and my cat died

when I had lived with her for only three

months, who has the right to be

most sad?—which is like asking whose silence

is loudest: that of the blank sheet at the end

of Finnegans Wake or that of Joseph, who has not

one word recorded in the scriptures.

In Dawson City, the Klondike, cellulose nitrate

strips of silent film unspooled for years, waiting

for light, to tighten again around another reel.

Sometimes they would spontaneously

combust, burn down the theater

that held them, raging on even when

completely submerged in water. The French once

called their army la grande muette, the great

silent one, because they had to suffer

in silence, but in Dante’s Inferno, the damned

suffer according to the principle of contrapasso

like the man in Missouri who killed

hundreds of deer and was sent to prison,

sentenced to watch, each week, the film

Bambi. Let us observe a moment of silence

and then book a room in the hotel

Relais du Silence, where we can engage

in Perpetual Adoration: human

trances, human nectars, ensuant

charm, a transhuman surname

chant. On the wall of the cave

painted twenty thousand years ago

in Font-de-Gaume, a reindeer nuzzles the flank

of stone. In the fresco above the sanctuary of

San Damiano below Assisi, after the cross speaks

to St. Francis, St. Luke the Evangelist pours words

into the head of a smiling ox.

Lost Again, Monte Perdido, Mont Perdu, Wherever

you’re off to now, a single-strand pikake lei

swaying between breasts: Aloha! Just pretend

it’s the transhumance, sheep threading their way

up your jagged crest in their grey woolly-rag

lollygag as if they were the basting stitch

of a god trying to figure out how to hold

everything together. The sheep, called brebis

on the French side of the border, pick their way

among stones littered along the peak where

someone must have emptied their pockets as if

it were a vide-poche tray, as if the sheep crept

in some trans-human trance across Germany

and Europe where the living step around to avoid

walking on the 40,000 permanent brass markers

embedded in the pavement: stolpersteine, stumbling

stones that announce where someone who was

murdered in the Holocaust once lived. When the sheep

look up, a bit of clipped grass remains

on each one’s lip.

Pas Encore

The late summer grasses say

not yet, which is never

the same as nyet, just as

Galileo, after being forced to

recant his claim that the Earth moves

around the sun, murmured

E pur si muove, and yet

it moves. Even the name of

your perfume, like the late summer

grasses, says not yet, but it’s the smallest

island on the Seine that’s named

Paradise, and at the almost end

of your breast is the only pink

I can find in this late fall.

Angie Estes is the author of six books of poems, most recently Parole (Oberlin College Press, 2018). Her previous book, Enchantée (Oberlin, 2013), won the 2015 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Prize and the Audre Lorde Prize for Lesbian Poets, and Tryst (Oberlin, 2009), was selected as one of two finalists for the 2010 Pulitzer Prize. Chez Nous (Oberlin) was published in 2005, and her second book, VoiceOver (Oberlin, 2002), won the 2001 FIELD Poetry Prize and was also awarded the 2001 Alice Fay di Castagnola Prize from the Poetry Society of America. Her first book, The Uses of Passion (GibbsSmith, 1995), was the winner of the Peregrine Smith Poetry Prize. A collection of essays devoted to Estes’s work appears in the University of Michigan Press "Under Discussion" series: The Allure of Grammar: The Glamour of Angie Estes’s Poetry (2019).

Matthew Cooperman

A Little History of the Panorama

Matthew Cooperman / text

•

Simonetta Moro / drawing

thy portioned land

/

the eye can see

I: Claude Nicholas Ledoux, “The Creating Eye,” 1804

A thought of human scale, of the Cité Idéale, though it is late in

the night of the eye. Evolved toward salt, an architecture always

more detailed, more colossal. The eye radiates, apse and gate. One

day it is stalls for taxation, and the next, comfortable seats for the

polity. Whose neighbor, what neighbors, sometimes the whinny of

horses. From the sky it is a new carnival and the gates are

perpetually open

infinitesimal lash

colossal taxation

taking it / the apse

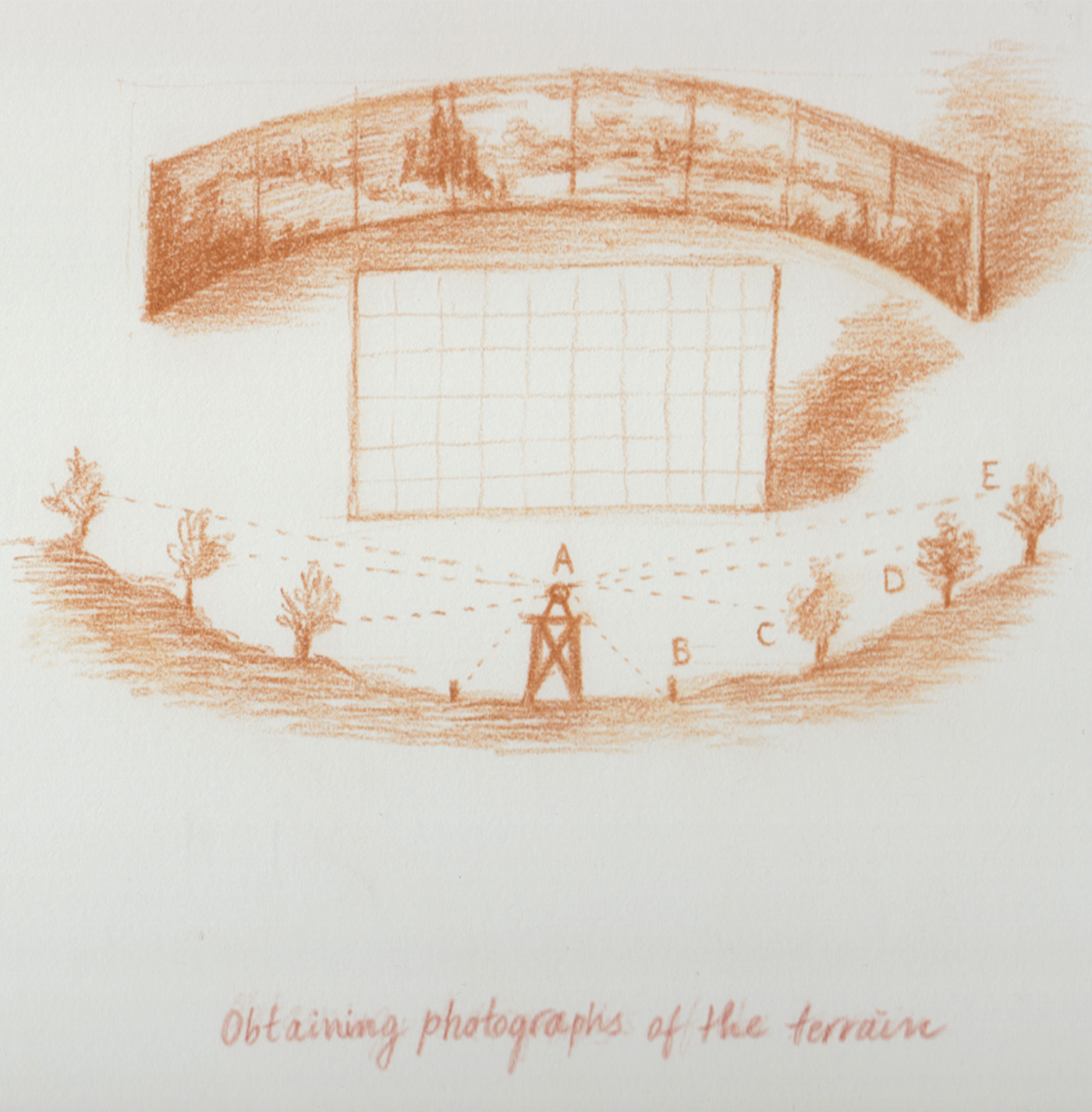

II: Obtaining Photographs of the Terrain

A grid laid upon reality, qua Wittgenstein, something abutting the

eye as much as the brain. As equal the brain the span. It is a grid

of trees and park legends, canals and tunnels for the epochal

subway. Relief must be extended. In the silvery dawn, a specific

nostalgia for the felt models of childhood enters from the left.

A.

B.

C.

E.

III: Panorama Painters at Work

Crosshatching too, at work. Representation in the grip of the

thumb. Are the men on their scrim scaffolding. They throw their

hands up before their eyes (perspective, height, rising azimuth).

Glorious in the X, which is a bond to time, they build a monument

to observe nature, and make a part therein. Strut by strut, the sky

goes up. One poor soul has broken his wheel. The sky will be too

elliptical.

relief

as equal the sky

the spin

history of looking into

upon

felt models of childhood

seeing one poor soul

to a common

walking here the beginning

and necessity

impossible object

to resist

social blazons unions to resist

sociology privileges

slowly the representations

epoch the same

advent of number democracy genetics

quantified heroes name

to a common

no one

IV: Hanging the Panorama in the Rotunda

It is an order of pipe cleaner trees, enclosure acts, free will and

wandering. It is the faux wildness just beyond by which

civilization thrives. Someone is making a surface, a dry wall. It

requires great skill in mortise and tenon, lost art of whittle and

bore. There is a reference to salt on the brow of the worker in

thrall to the wine press set in the village square. In others' words

and distances, the war far away, the body estranged, the classical

form from the rustic, the marble man from the child.

hammer the whistle

in wine

iron or

ire aye

the yesses implicit

in cinema

“the age demanded an image

of its accelerated grimace"

It is

an image

of work

and the end

of work

V: Cast Iron Frame of the Panorama Building, 1873

Thus carried away, if not beyond space and time, then from

everyday life to a moment thirteen years ago, a place 100

kilometers away. You, by the well, tumbling pinecones, a visitor

from the future casually changed from passerby to eyewitness. Are

you sighted? Am I able? Significant events, roving planets. She

finds himself surrounded by terns, ferrous earth. In the depths

below lie the forgotten hamlet. The compulsion for illusion

becomes all the more obvious in the next few sentences.

seeing as what is being said

is building what is being seen

Matthew Cooperman is the author of, most recently, NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified), w/Aby Kaupang, (Futurepoem, 2018), as well as Spool, winner of the New Measure Prize (Free Verse Editions, 2016), the text + image collaboration Imago for the Fallen World, w/Marius Lehene (Jaded Ibis, 2013), Still: of the Earth as the Ark which Does Not Move (Counterpath, 2011) and other books. His seventh book, Wonder About The, winner of the Halcyon Prize, has just been released by Middle Creek Publishing. A Poetry Editor for Colorado Review, and Professor of English at Colorado State University, Cooperman lives in Fort Collins with his wife, the poet Aby Kaupang, and their two children. http://matthewcooperman.org

James D'Agostino

Nativity as Pietà

“That’s how Fakenews is born.”

—Dmitry Polyansky, First Deputy Permanent Representative of Russia to the UN

no windows so the snow is

glass before it lands

steam from the sloughed-off

face of the hospital bombed

the pregnant mother stretchered

out atop a strawberry blanket

hauled from inside in between

the blast heaps in between her

breathing who says to the medics

when she learned her baby

wouldn’t live kill me now has died

as in between breaths the UN rep

from Russia says this hospital

has been turned into a military object

bombed in between his cease

and fire in between an acre of land

50,000 pounds of strawberries

can grow which aren’t they called

by how carefully they’re held

above the dirt by straw by hand

Reading the Bible Upside Down and Backwards

Reporter: “Is that your Bible?”

President: “It’s a Bible.”

It begins quickly come I surely saith things

and ends with God beginning the in.

And once the in begins, Moses opens

up the sea to let the army of the drowned

out. In the upside down and backwards

Bible, that first false idol calf puddles

back to plain old gold again, a little pat

of butter. The upside down stone rolls

back into place and reseals in Lazarus.

Jesus wipes spit and mud from the eyes

and blinds a guy. The crowd lolls until

louder and louder the multitude growls

around a single fish. In the upside down,

in the backwards, in this inverted perversion,

there is no vaccine for obscene, for kneeling

with protestors only to load gas canisters

that skitter and bounce up the ceiling

of the street, leap back into the arms

of the National Guard. In the upside

down, George Floyd floats above his

murder, a flag in no wind, only now

his stock-still killer’s pole-driven in

the poured cement of Minnesota sky.

And we haven’t even met halfway yet.

The beginning and the end only ever

touch in the middle of the street. And

I just learned the verse at the exact center

of the Bible is in Psalm 103, my soul:

and all that is within me. I just learned

less lethal’s the name that’s vetted by legal.

A dozen burning cities might be multi-system

inflammatory syndrome, but each case takes

a tremendous amount of resources,

so maybe when the smoke clears your

dumb lung might learn something.

Not Coming Back

Late summer stem scruff finally drops

from the gutter onto page ten of your book.

It’s a ballpoint Kandinsky coltish squiggle,

more a trot than not, but springy, a-dance

askance on the poem that ends with a riderless

horse, trespassed field at night, and your death

as you imagined it. What I first thought

unknown funky wing design, became one

butterfly carrying the corpse of another past,

then came to rest as a mating pair, startled,

but not yet done. So one flies away and

the other goes dead weight ballast sandbag

so as not to fight each other going nowhere.

Late Sunday light might even make you again

taste the peaches not coming back, but it’s why

peaches end in aches—stomach, heart, summer

stars, somebody—don’t let the bough go

and smack you on the spring back.

—for Dean Young

1955-2022

Song to Survive the Spring

Moth a dead moon down left

corner of the dormer.

A necklace of sprinkler strewn.

Another noon takes off all its shadows

and just stands there.

Look, it’s Lorca’s

corneas.

It’s part of the world that hasn’t broken off yet.

It’s connotation and detonation. Rain,

the least adhesive.

What are we

sentences?

I me you your my mine.

Glass stained sky

and the black gouges punched out of it,

crows.

Orpheus Upshore

It's not I can't sing it,

it's it ain't a song, not

for long. It’s not

another world, it’s daylight,

an ad hoc vatic havoc

we are going to

call okay weekday.

Squirrels chase tree

to tree like the neural

pathways of a pretty

good idea, and later

claw clatter around

a walnut trunk’s

cracked bark sounds out

water down cement

steps. For a second

what floods in isn’t

the basement or rain

but that time for hands-

free seeing I held in

my mouth the flashlight

that one sudden moth

went wild over the end

of. It was like French

kissing death right there

in my lit skull skin mask

and the strobe pulsed

shadow of it on

the floor kissed back.

James D'Agostino is the author of Nude With Anything (New Issues Press), The Goldfinch Caution Tapes, winner of the 2022 Anthony Hecht Prize (Waywiser Press), and three chapbooks which won prizes from Diagram/New Michigan, CutBank Books, and Wells College Press. His chapbook, Gorilla by Jellyfish Light, is forthcoming from Seven Kitchens Press. His poems have appeared in Ninth Letter, Forklift Ohio, Conduit, Mississippi Review, Bear Review, TriQuarterly, Laurel Review, and elsewhere.

Lindsey Webb

I. Garden

Locke sank into a swoon;

The Garden died;

God took the spinning-jenny

out of his side.

—W. B. Yeats

Sitting in a garden, unsheltered from the moon’s

ongoing description of the sun. A coyote walks up to a

flowering pear and sticks her head in. Hibiscus spends

at least part of the night describing the moon.

If heaven will one day arrive on earth, as Joseph

Smith said, will it appear as a grid? If women don’t

speak to God in heaven, what will they say when it

falls to earth like a curtain? You float past me above

the leaf duff, “clean” like a ghost, “clean” like a

difficult vessel.

The garden tells its lie of isolation: “nature has died

and the garden is its memory.” A blanket of cool

irrigation settles in the corners of each leaf. Ghosts

and rabbits, horned lizards, carpenter ants organize

their respective diplomatic anarchism. I take a

different path, almost running— disturbed by all the

roses facing forward, as if I’d set them out myself.

When we were younger, I complained I had no sisters.

You, taller and prettier, turned your dark hair around

a finger. In a silly voice, you said: remember, I’m your

sister.

Older, I forgot. I, forgetter.

Lindsey Webb is the author of Plat (Archway Editions, forthcoming), and the chapbooks 'House' (Ghost Proposal, 2020) and 'Perfumer's Organ' (above/ground press, 2023). Her writings have appeared in Chicago Review, Denver Quarterly, jubilat, and Lana Turner, among others. She lives in Salt Lake City, where she is a Clarence Snow Memorial fellow and PhD candidate in Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Utah.

Terese Svoboda

Drowning in Sound

Plunged, the surround

robed like a neoprene sidestroke,

ear in.

Close your eyes, their imprimatur

too much. The walls fill with color.

Boat motors rise in their roars

like the hinds of whales

out of the depths of time,

wrong closet. You will be saved

by silence. Tuesdays were the best,

says someone in Amharic,

nostalgic in the midst of a storm

in which he can't do anything

except talk talk talk.

Waves cymbal at the glub

in your ears, the wind changes

its outfit, scanty and teasing,

so metal – you dog you –

the sides of the boat

slick, no one on deck,

rescue too near the ear:

now trombones. Both ears. Some real

angel person unavailable, some bad

lesson in sound, or drowned.

What Counts and What Doesn't

“The anthropological machine...that depends upon...the distinction between bios (or political

“form of life”) and zoe (or “bare life”) – Giorgio Agamben, biopolitician.

nature has no need whatsoever to value us

forget the v.v.

Haraway deploys the term “fingery eyes” to describe a human looking at

a moss-covered stump that resembles a dog

the animal stares back such reflection

killing fish/harvesting fish

you not being a fish yourself, how can you know its pleasures (pains)

patches of scales floating on the surface of the water (a tell-tale sign

of the presence of herring) sometimes look like ash

to us

the inversion: that cattle are treated like people

insults the memory of the dead or not

this radical alienation of the self

mitigates

the author’s tendency toward ventriloquism or the well-intentioned objectification

necessary

when one tries to “speak for nature” or let nature speak

through oneself as an author

the uncanny presence

of polar bears, stuffed, standing in the study

You Can't Not Talk About Waves

Little machines of stay and go.

Up and over, the atoms pound you and your board

into place, while the crest orbits

to match the column of water below.

Oh, yeah – there's hurricanes when

waves Peter Pan the surface to elsewhere. But mostly not.

Every language sees their undulance

and repetition, and postulates, trough

by trough, a position forward.

Enter sailors, fishermen, Noah,

women who keep

the lights: ask them about the waves,

about the ragged dark that overwhelms their boats

or the giant jellyfish dangling its transparency to and fro

bobbing genitals

with burning

whips.

A wave in a vacuum – electromagnetic – must run into something to be known.

What do you call that noise? A sound wave.

Swells: waves unaffected by local winds

but from somewhere else

or from

a long time ago.

He sure was swell.

Go ahead, throw up.

The waves aren't done with you,

they're in your pulse, the shore is beaten.

The moon/sun causes our oceans to bulge: that's a tide a/k/a wave.

WWII WAVES. A moon

near Saturn

called Titan, its wind-driven waves on hydrocarbon seas.

Kristen Hanlon

REQUITER

requite v [re- + obs. E quite to set free, discharge, repay, fr. ME quiten — more at QUIT] 1a : to make return for (as a kindness, service, benefit) : REPAY, REWARD b : to make retaliation for (as a wrong or an injury) : AVENGE

Webster’s 3rd International Dictionary

She waged a war for

love; she waged labor.

A new commerce was borne,

call it “the gift economy”—

labor of love. As in “mother”

which means tethered to others

in this and every tongue.

Sleep debt cannot be spent down

or paid in full; it only

carries forward.

She woke from the dream

of a sixty-four-page poem

to Mama, I’m wet.

4 a.m., child back in bed,

she lies down again,

wistfully tries to re-enter

that dream. Instead,

a cold warehouse

full of books, none of which

bear her name.

In the plaza she wonders

What are police for?

It seems the perfect day

to avenge her loneliness.

Her hopes revised so often

she is almost a stranger to them.

And what, exactly, was at stake?

Leaf, brick, arm’s length transaction.

Dark with responsibility,

dedicated to industry & thrift.

The wolves wore uniforms

& guarded the banks.

Meanwhile the quotidian

incites crowds to sleeping or reading.

Unfolding action is what they desire.

Hope is the thing that weathers.

Watchless, she checks her phone

but her phone is dead.

Timeless, she is free if uneasy

to wander.

In the plaza, a bit of violent speech

followed by laughter.

Requite or quit, the moment

seems to say.

She turns away

to find a bus home.

The sleep debt is constant

it carries forward / it is real.

While others are being

teargassed in the plaza

she is folding laundry,

watching it on TV,

hearing the helicopters

in real time, their echo

on the live feed.

It is a warm night,

she could reach out

the window—

If you’re going

to the North County Jail

where florescence flickers

on the booking line

remember me

to one who waits there

she remains

a comrade of mine

Rest was something

to resist, like arrest.

She pledges allegiance

to the oak leaf,

is given short-shrift.

$122 left in the account

of which $61

is uncashed checks.

Yesterday’s winds

were casual.

Today’s seem filled

with intent.

She lies awake, obsessed with seven-letter words.

Purpose and persist, forfeit and strange, silence and obscure,

apology and regrets.

She might fix her own name to the list, but refrains.

Migrate and arrival, elegant and haggard, desired and settled;

anomaly, refusal, liberty.

Revenge.

To requite one must let

competing impulses

collide. What’s worse:

to be ignored, or actively

thwarted? In a sea of so

many arms, three guesses

may be the most

you will get.

Was ardor an enemy?

Having ventured there,

having been refused

(requite or quit)

(more at: QUIT)

Desiring more purpose, more perfume—

There must be another way to live

Kristen Hanlon is the author of the chapbook Proximity Talks (Noemi Press). Her poems have appeared in Colorado Review, Volt, New Orleans Review, Interim, Aspasiology, Posit, failbetter, and elsewhere. She lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Katie Naughton

the question of address

I know you were there

in the time I passed

through spent

in places and time you

coming near me passing

away. I know we spoke

worked alone or together

in a room or outside

while the day while year.

I may have written you

or spoken

more silently in time.

What was your voice?

Was mine? I remember

some of you and some of you

I don’t but mostly I

don’t write or speak

to you anymore.

I write these poems.

I put you in here.

The places we were

are still as vigil. I open

a window slight hear

the traffic come inside.

the question of address (poem for a scientist)

you the ideal for what I want

to tell you, you

receiving beyond reception.

I make myself

present to you

(trying to keep thinking)

Sometimes you’re someone. Some times

’re someone else Some times

some things surround .

(The kitchen, where I fell in love with you in love with a widower and his three-year-old son and making me acorn squash with sheep's milk manchego and some other fall vegetables, how I went home to New York and knew on the north side of Houston walking west past a small garden on a wet day with a former lover that I was waiting for you, which I did, happily through the winter, though it may not have looked anything like waiting to me or anyone else.)

This letter misplaced is wrongly dispatched

(thinking is self ish takes me a long time)

the question of address (poem for a scientist)

Nietzsche saying all philosophy is autobiography, by error.

Or Keats the reverse "Axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses."

And science tries to erase you from it but cannot;

(Your life in it, your hours at the lab, your slow laptop borrowed from your mother from her psychology department running and crashing the hours of analysis, the method you used nearly obsolete by the time you finished the writing, shows the history of your funding, your advisor's relationship with you and with his department, your perfectionism. The time spent cooking, making wedding cakes, spent on the shady shore of a small lake with me on Sundays, spent taking pictures of birds in a nest, spent in and out of trains and cars and airplanes to see me, your mother, your brother and his daughter. Everything you felt obscured in science's passive voice. Science obscured it. You obscured it. But the work is yours. Your work to make it yours.)

(I am in it, too, how I hated it, waiting for you at the window of your lab at dusk, throwing sticks at the window lit with you measuring reagents and mixing media for your yeast cultures to grow in, your unwieldy anxiety about starting and finishing, how we could not go anywhere because of it, how you were never done; but also loved it, being let in, the big oak door, Yale's old stone castle of an environmental biology building, to your brilliance, the warmth and light in the messy piles of papers and stacks of jars of coffee growing mold, waiting for you there, and all it gave me access to, in my wool sweaters and leather shoes, my tidy intelligent face and well-kept hair, passing unnoticed into the libraries of the academy their dark and bright wood.)

(I am there but no one would recognize me, nor am I the subject of your work or object of it. Here you are.)

If you were here, I would have told you everything I could say

a gift and what I extracted

lost, little bright fragments propositions

something like texture

a life with without you

addressed in terror

What else could I have written? :

the question of address (elegy 4: suburbs)

some questions never leave the garage the basement

the hedges and other plants circling the house

the rock wall stratifying the small hill in the back yard

between oaks and wax begonias

a house can be a place you never leave

it can be the hatch door to the basement

the bare construction of stairs

a place to carry a bicycle up or down

a machine no more beautiful than complex

the asphalt path outside domestic enough

a thin layer slowly shaped by roots as dirt would be

as the oaks grow summers come and go

tracking back and forth that route between basement

garage past plantings past a screened porch

a neat lifetime of things the cared-for cars

every license plate marking state and time

lost aesthetics of childhoods grown quite old

the small secret half-room a ledge under the stairs

still possible to climb into a house within a house

a room within a room stooped ceiling short table

the time passed there half-outside half-inside a family

the question of address (elegy 5: mill city)

orange clawfoot tub

bathroom sink in the kitchen

dentures in a plastic deli tub

linoleum

fifty-year-old gas stove faulty pilot

percolator coffee

toast crumbs

Polar diet soda orange dry

window full of cactuses

refrigerator magnets the American Southwest Alaska Catholic holy places

rounded edge of green beer refrigerator

galley kitchen tight and dark

Tom’s trying to tell eighty-year-old women how to wash dishes

the glasses I took the pots and pans

once no one lived there before the stuff was gone

the washing machine and dryer

took three old cousins to take it out

a few steps down the cellar stairs

back up the stairs and out the kitchen door

the dirt floor basement

stacks of sheet metal and the tools to work it

Cut once measure twice

burnt out old apartment towards the back

had linoleum had windows had a family of cousins living in it

before they moved upstairs

wet burnt dirt and oil smell

Ballentine green can

bright sharp yellow smell

cigar smoke

it’s naptime

hating naptime

Kelly green suit for Sundays and holidays

old leather chair hard red leather

I take a birthday cake towards it

you don’t have to if you don’t want to

Ballentine green cans made into a prop plane hung above it

brass bent into model tall ships on the table next to it

how to never move all day

shelves and lost shelves of frog figurines

big jars of hard candies all taste like mint like fruit

I aspirate one once lay on the couch with the knot of it against my spine until it is gone

the pictures of the cousins the grandkids the big eighties high school hair

a white ceramic cat a candle never burned smells like wax roses

one room in the back I never go in

one room in the back the old things are in

dungarees swim suits sweatshirts from Cape Cod

above-ground pool round and cold

sharp and bad smelling grass the roaming dogs of the neighborhood the city dirt

the sidewalkless road the crumbling asphalt the hedges torn through by a small tornado

the bird bath out front the porch the stairs to the second floor

the cousins the motorcycle on the front sidewalk the hot vinyl seats

the poison ivy in the lattice shiny and green

the bedroom a dark place dark wood and worn down dark red woven mat on the floor

when I sleep here I sleep in the bed too

spiral curl of carved wooden banisters

spots in the tiles of the ceiling

I watch TV from bed eat a piece of gum all the way through

do you want to go to 7Eleven now? //Is it time yet?

I get sick when we are downtown lie in the bed while the people are talking in the house

the dresser where the things are lipstick the jewelry I am given

the blue glass votive light the Virgin

the mid-century photos

Peggy Ann

in nurse’s whites

John Joseph

an army mechanic

your father

with a radical’s facial hair

when it’s night the streetlight through the windows

the porch is there

the front door opens to the stairs the dark indoor stairs to the cousins upstairs

Aunt Jo’s, David Dodge.

there is not really a front door to downstairs, the entryway opens to the bedroom

we come in through the front the bedroom or we come in through the back the kitchen

there’s a key under the mat in the back

Katie Naughton is the author of the chapbooks A Second Singing (Dancing Girl Press, 2023) and Study (Above/Ground Press, 2021). Her poetry has been published or is forthcoming in Fence, Bennington Review, Colorado Review, Michigan Quarterly Review and elsewhere. She is an editor at Essay Press, the HOW(ever) and How2 Digital Archive Project (launching in 2023), and Etcetera, a web journal of reading recommendations from poets. www.katienaughton.com

Jory Mickelson

Plunder: The Company

Under every green tree

a burning of measurement

in cord & board foot, in tons

of ore: gold, silver, lead.

Seven pounds of meat

per day, five pounds of flour

per week, the contract said.

Timber needed to build

the works, to build the mines,

to build the town, the tracks

running out. The smelter eats

seven hundred cords of wood per day,

devours all the ore someone

can bring & more, refines nature’s

handiwork with heat & cyanide,

releases what shines within.

Friday Night, Bannack

Because the cowboy asks me to, I rise

in the smoke-filled room. We greet

shyly as at the start of courtship, hats tipped

back on our heads—moons behind a cloud

of hair, then we step hard through the fiddle’s

unremitting saw, the pressbox’s exhalation,

a song that raises our feet despite the long

hours in the saddle or the mine, work

that’s given us our rough hands. But these hands

can’t offer relief with such delicate maneuvers.

The failure of women to appear—the ones

we left at home across the country, who love us—

or will someday. We will build toward that

hour of square wooden buildings, window glass, lace,

where a woman is fit to be seen.

We increase

our speed as the tempo builds and the rollicking

of our bodies pressed like slices of roughneck bread

sandwiching the tune between us. Our

sweat sluicing us in salt, in musk, in cheap

liquor coming out our pores. The man who asks

is the man who leads over the rise

of the melody’s swelling. Each step

stamps our desire into the gapped boards

of the floor. We shed nearly all at the spin—

the work and what this way of living’s made us.

What distance did I know?

The pacing of the river from

the house, the expansion of my father’s reach

year by year, beyond the town, the routing of supplies like water

wending its way from maker to boat to seller’s

hands. The extension of the priest’s orans, the floating lace,

the hang of the chasuble’s dull gold. The breadth of the voice unfolding

my imagination from Antwerp to

the New World. Red dirt of Kentucky, the Cherokee,

the crumbled empire of Napoleon, given away, the West. What could be

done at twenty, or in just twenty years?

The journey beginning with an island. Begin with

a stretching of the neck toward horizon, with a vessel, the sea.

Rivers and Mountains at the End

If I believed in heaven, it would be

some low-slung valley with scattered

pines & strands of gold-gone aspen.

Some patches quaking in wind, some not

& sometimes on the same tree

& since I am dictating belief

I fill my creed with a cloudlessness

so blue it’s mistaken for a movie set

for some old picture, when picture meant

film & because I can’t get enough—

the valley rills with blue, go ahead

and choose lake or pond or meandering

oxbow. I pronounce this dogma:

we believe in one valley free

of smoke, no wildfire or flame, no burnt

offerings, also no development.

Let old heaven & its many mansions all

recess into ruin, even the great old

gate. Let it fall into earth, become

artifact of the previous age. But even this—

one person’s uncertain paradise too

is a failure, limited & I am aware

& yet, it’s still mine—

a kingdom yet to come.

Slowly Now the Shadows Lengthen

Soon the deer will come

to the pond. The pinks

of their tongues cooled

by water—they strengthen me—

I would call this desiring home

Let your figure tarry

with me, ghostshape

in my remembering. I am lonely

without your silhouette quickening

the night star. You are with me

when I close my eyes. Rest

your head against me

like a teal hen set

in the sleep of her nest.

Upward and trackless they go

my words parting nothing,

not distance, not longing.

Prayers scatter like chaff,

the fade of ember rising.

This isn’t paradise

though it would be easy

to believe in if you were

beside me. A kingdom

is just an emptiness

unless there is another

with whom to divide it—

heavy, bitter-skinned

wild summer plum

honeyed to its stone.

Jory Mickelson's first book WILDERNESS//KINGDOM is the winner of the Evergreen Award Tour from Floating Bridge Press and the 2020 High Plains Book Award in Poetry. Their work has appeared in Poetry Northwest, Terrain.org, Court Green, and The Rumpus. They live among the moss and the mud of the Pacific Northwest. To learn more about them and their writing visit www.jorymickelson.com

Jackson Wills

Baltimore

How do you people get to the other end of the day?

With the lights off I can notice that autumn has a higher pitch

coming in through the window now, summer’s drone and growl interplay

abandoned for the cleaner sounds that hiss and scratch,

the fizzing leaves, the leaving car trailing,

my baby snoring through a cold, warm on my lap,

the trees whispering contending with their sap, the swing’s jangle rising then failing

as the leaves subside their effervescence and I can hear the pavement

where feet and leaves move down the street to a point

and are lost. This beautiful night I feel partitioned from these moments;

separate from all world; my eyes are out of joint.

Earlier, worm dragged black across the wet walk,

with a wake like a finger on a mirror,

its gills stripped off of mucus felt like chalk

in its little worm soul where the segments get near.

Where the salt climaxed into a mountain

the car camera had clotted with rain.

I can only be inside now of a moment that I hate.

I held the umbrella ineloquently bent

over the parking machine. Why can’t

I think of someone else I know but

I get sick? My mind is full when I resent.

I lingered at the warming bathroom vent.

Dreaming is at best ambivalent respite:

southern marshes spotted with dying white horses,

and eagles riding waves where the estuary forces

ocean that I’m agog at with the strangers on the dark sand spit.

Always the waves come up to the upper porch

and we huddle there with the family I never see as waves approach

and drop after awareness disappears.

There’s sickness there that matters less because less clear,

but I mostly would send back my dreams,

my inside images mostly just a queasy cram

I’d crawl from. I’d sleep if it were black indifferent cream.

In the morning, my autumn daughter in white light feels watched

and quoted, and it’s raining orange needles on the girl.

The maples contain us in cathedral splotches,

furious lizard orange, and the baby bending down goes slow to touch,

as she stooping separates the pebbles in the loch water,

and a wasp mostly swamped buzzes sideways in the lapping

toward us and she gets afraid with laughter,

then settles down to silence to watch damp flapping

rehabilitate the bug, but I’m not there.

He’s gentle with himself like he’s a pupa.

I can no longer participate in the beauty of the world.

Thoughts Other than Whiskey, and a Heron in the Snow

I would kill for any other thought than whiskey

I could be induced to kill perhaps too easily

The heron flies over the frazzling bluff

of snow below the stubbled field of dead corn plants

Stiff brown sunflowers, corpse faces of seed,

hold snow in leathery rows

Brown battalions tickle into distance