Listening In on a Dawn Springtime Walk by the River Dart with John Levack Drever and Alice Oswald

C. 5am, 6th April 2012, Ashprington, Devon. Recorded by Drever.

Transcript:

[Inaudible for about two minutes. Leaves and branches crackling.]

AO: …It is very interesting what you were saying about those recordings [the recitation of Memorial for CD] lacking in ambient noise, it makes it very dead, doesn’t it?

JLD: Well, I’m kind of a believer in that although background ambience can be silent, it still actually signifies a lot.

AO: Yes, yes. The clock ticking and we always go mad…

JLD: I guess it makes the voice massive and it is also so close-miked.

AO: I suppose it’s meant to sound [as if] it’s in your head.

JLD: Were you in a kind of booth when you...?

AO: He let me do it all in one go. I hate that thing of stopping and starting.

JLD: That’s what I was going to ask, the listener will never really know, but you assume that there were multiple takes, kind of Glenn Gould style.

AO: Whenever there was a turn of the page, I just made a long pause, which they edited out.

JLD: You didn’t listen back and agonize over one word here and there that sounded a bit odd, not that is does?

AO: No, I didn’t listen. When I did Dart they made me go back and forward.

JLD: I liked it. Was there a director, editor?

AO: Yes, they’re editors, not directors. Then you have to bow down...

JLD: Then how else do you do it, though, unless it’s a live performance?

AO: Yes, I did it live at the South Bank and I much rather they recorded that.

JLD: Memorial?

AO: Yes, because when you are speaking to an audience, it has meaning in it.

JLD: It is the same as music, there is a performance practice.

AO: Yes, does recorded music sounds very different?

JLD: There was this kind of historical moment when performers like Glenn Gould… one of the first solo performers to get obsessed with the recording studio, actually gave up doing live performances in front of an audience.

AO: Really? To me that’s all about striving for some perfection that shouldn’t really exist.

JLD: Yeah. Weirdly, he used massive amounts of edits. And he kind of shunned the audience. But weirdly, in the recordings you still hear him singing away to himself. When he’s playing. He’s a terrible [singer]...he’s playing Goldberg Variations but going [approximates Glenn Gould singing along]. So that survives. It sounds odd. It’s kind of a trademark.

AO: I started writing a novel. I got really interested in this case in America. Where someone committed suicide, and the family went to court because they said that the cause had been listening to pop music.

JLD: Eh? Marilyn Manson or something.

AO: It was saying that the record, when you played it backwards, it was saying “do it, do it, do it.” And there was this big case. [Someone] played another of his songs backward and it said something like [inaudible]. And I just got really interested in the idea of a court case based on recorded sound. And the idea of…

JLD: Audio forensics…

AO: … recording angels recording the whole of someone’s life and then hearing what’s going on as a subtext. So what...I’m trying to spend my time interpreting noise into language. It would be interesting for lawyers to try and work out someone’s everyday life and what the noises are actually saying to them.

JLD: I heard a sound work recently by Christopher DeLaurenti [Of Silences Intemporally Sung: Luigi Nono's Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima (2011)]. He got hold of the old Deutshe Grammophon’s recording of the La Salle String Quartet performing an Diotima (1979-80). A very beautiful string quartet. It’s an interesting work related to poetry as the original Nono score has text by Hölderin, that the string quartet members are supposed to read as they are performing, but without saying it. Anyway, this piece is quite interesting because it’s an old recording of a string quartet that has lots of long silences in it and is quite noisy. DeLaurenti, who’s edited the recording to produce a new work – he’s a kind of soundscape recording artist. So, he’s got really interested in those little gaps in between. And, for example, the recordings of the performers tuning their instruments on the fly and those little moments and all those tiny gaps. Everything but the Nono piece is left, basically.

AO: How wonderful. A Sleepwalk on the Severn which was quite a weird piece which a lot of people didn’t really get...The structure is meant to represent, it had these poems that bled into prose, prose is meant to be the kind of rumblings and mutterings you get around the poem, don’t you? Because I always think that a poem is the last most emphatic thought. And if you could kind of...poems work by needing silences and that’s what their punctuation is a kind of musical notation of silence. And so, I’ve always been interested in the idea of picking out what’s in that silence, what kind of voices are going on that are preparing for the next line.

JLD: Because the poet is present in that piece, or work. Or do you, is that you, or just an avatar or something?

AO: Yes. It’s me secretly slipping in, the recording...kind of pedantically trying to record the landscape. People couldn’t really make head nor tail…

JLD: Well, I like it a lot. I like that it makes it more, well it makes it less definitive as well. It’s like you are trying to endeavor to do something.

AO: I think that’s what people, what the mainstream poetry world it quite, they like very perfect texts.

JLD: Whereas the Dart is such a strong title. It’s like a kind of, … it’s not A Dart or Some Darts, or, not that I am criticizing but it works on a different,…

AO: [inaudible] interestingly a different way to do it, wouldn’t it? Your Darts.

JLD: Well, they do. You do present multiple...

AO: Multiple voices, yes. So, it’s meant to be kind of protean… So, your practice is all about lack of definition, though, isn’t it? It’s about process rather than, of such imperfect pieces going into a work, is it? It that too specific?

JLD: Erm. I don’t really know. Mmm.

AO: I suppose any experimental practice…

JLD: Well, I like to sound somewhat random on one level. Although it’s very common actually in this kind of post-Cagian [John Cage] world, where you’re often faking a level of randomness.

AO: [mostly inaudible, talk about the landscape of the walk] Sorry, what were you saying, post-Cage?

JLD: Yes, you make it sound as if it were a bit random but it’s not completely random. So, it’s a level of messiness.

AO: Yes, I think I deal with that as well in language. But it’s not that it’s artificial messiness. It’s a form that allows something other than itself to come in. So that the author mustn’t dominate the piece completely. My kind of model/structure, was always kind of the Japanese Noh play, it’s really interesting that thing where you have a conversation going on between people and then a god or something from the other world appears close to a god. And to me, it works like that and you have this kind of rational, kindling dialogue and something that summons something that is not the poem but detects a poem. I [am] interested in the kind of poem that shivers when something from outside comes in that you are not in control of.... It’s like a tidiness summoning a messiness.

JLD: So, then I guess you’re then revising, revising…

AO: No, not really. Not unless, [there is] more than when I started out at first.

JLD: So, it’s more improvisatory.

AO: It’s not revising, it’s that it might take a hell of a lot goes to get the right question that will bring the right answer. It feels like my working practice is a form of listening to the voices in my head and it's as if I mishear it when a poem doesn’t work––I haven’t focused enough and heard it. It’s like listening really hard to silence.

JLD: An internal…

AO: An internal silence. I was interested in getting right back at that to people that generate texts from listening to the muttering in their heads.

JLD: You know there’s this myth about Mahler and you can see it in this Ken Russell film [Mahler (1974)]. Mahler’s kind of composing, and you know his first job is always to make a hut before he started working on this symphony, to build his new hut in this really idyllic location during his holidays.

AO: In order to work there?

JLD: Yes. He had the most idyllic hut and this lake and so…

AO: Is that because he’s using the ambient sound?

JLD: Yes. In the film you see him being really inspired by the cowbells and the birds and the sounds of nature but then you see him trying to compose in the hut and he’s like really pissed off because it’s too noisy. He’s like: “Go away now! I’ve done my absorbing or my imbibing”.

AO: Is that true? What do you think?

JLD: I don’t know. I don’t know. [Yes, it was true, on one occasion he ordered the birds to be shot.] I don’t really mind if it’s a Ken Russell fallacy. I kind of like that idea that “I’ve had enough now”, “I’ve been inspired now”, “put my earplugs in now because now it’s the internal processes taking on...."

AO: It’s the hope that the mind has somehow recorded it…

JLD: Do you know Richard Strauss’s An Alpine Symphony? Because it’s really interesting, comparing it to the Mahler symphonies...because they’re both romantic, sublime type composers, but Richard Strauss took a very different approach than Mahler because he didn’t like all the symbolism, because Mahler immediately becomes whatever, you know the birds become children’s voices, angels, etc… and it’s all representative whereas the Alpine Symphony is you know, is more about climbing up this mountain in the morning and it's more about scale and exhilaration....

AO: Yes, that’s exactly what I was trying to get into in Dart. I don’t want the sound of water. I’d much rather find music that gives you that feeling of the same thing…. But your pieces are very interested in real sound, they do use, not representatively necessarily…

JLD: Well, it depends. That’s the problem with the soundscape, with the notion of the soundscape composition is that it’s a strange art form because it’s tacitly representational because you turn on the microphone and you make an effort to record something as beautifully as possible with the best mic for that situation and try not to have handling noise like I am doing this now, it’s going to be a terrible recording but you try to be invisible in that process. And then you do a bit of editing and make your piece. The problem is representation is, it’s missed a level of, what’s the word? Translation, or authorship I don’t know? And a lot of composers this quite famous guy, Matthew Herbert, he, I heard him talk a couple of times about saying in Mahler’s era, he didn’t have any recording devices. So, you know, he had to use orchestras to represent his experience with the countryside. But what is great now is that we have recorders so we can actually have that sound, so we’ve got nothing to worry about anymore and I kind of [think] that, that’s rubbish. Is that what Mahler would do now? Would he just run around with a microphone? And say this is a piece about my experience. So, this is potentially a very lazy medium, field recording. The cattle grids piece [Cattle Grids of Dartmoor (2005)] is completely different. And see, my Hong Kong piece [Ochlophonic Study #3: Hong Kong (2002-8)], which is now a completely messy piece which has been developing over years and years and years. But I now talk about that as being a really experiential piece, as me trying to make sense of Hong Kong. The fact is, it’s a really densely crowded soundscape.

AO: Is it a piece you just keep adding to?

JLD: Not anymore. There are very different ancillary pieces I think but the big city is kind of done now. The problem with the Hong Kong piece was that I’ve got such nice recordings, beautiful recordings. Very interesting recordings but every time I try to make a piece out of it, they become less interesting.

AO: That’s very interesting. That’s like Ted Hughes’ notebooks. There’s one book called Moortown Diary where he’s in the farmland and he’d just make notes everyday as he farmed and he came to try to makes the notes into a poem and he realized that whenever he did that, they’d lost some of their vitality. And so I think he kind of, it’s funny he did that book after working a lot with Peter Brook where he was doing a lot of helping with actors to improvise language and [then] happened upon something in his work that was about improvisation. That’s what I like about Sean’s [Sean Borodale] work actually at his best I think he’s doing that note-taking unedited.

JLD: Have you gotten a long way on, say, since the angel piece. [Angel: in which an angel sees everything closing in on itself at the moment of dawn (1997)]?

AO: It’s an uncharacteristic piece anyway for me.

JLD: Where every word counts. Where the weight you put on every word…

AO: Well, it was very Dartington, very Cecil Collins [painter based in Dartington from 1936-43], it wasn’t really typical of the way I write. I mean, yes, I suppose every time I do a new book, I change completely what I’m doing.

JLD: It must have been difficult going from river Dart to the Severn where it’s kind of a geographical travelogue…

AO: The trouble is, I always get asked to read Dart. I’m not going to do that. With the Severn it’s really much more about the moon and the tides than.

JLD: In this paper about you being, what’s the word, a gardener-poet? Or what’s the term you use?

AO: People like putting me in a box. I hope, I try to just shake up any labels that I am given. People are a little bit phased by Memorial it seems to have done something a little bit different.... Oh my god, look it’s a really high tide. Oh, you don’t have boots on. You’ll get really cold. I have never seen it that high. We could go somewhere else. That’s very interesting. It’s not normally that high. I’ve never seen it that high. But we could go down…

JLD: I can take my shoes off.

AO: It would really be cold. That would be dedication.

JLD: Very thin, the reeds.

AO: Very thin. They’ve got sort of areas where they have been trampled.

JLD: But as a very individual kind of thing. I was thinking about the acoustics of reeds because actually there’s … I was talking with Trevor Cox, an acoustician [see Trevor Cox’s Sonic Wonderland (Vintage, 2014) where he recounts an early morning encounter with JLD listening to Eurasian bitterns in Ham Wall, Somerset] and I was thinking of a bittern call, a very low-frequency call and it only happens in reed beds.

AO: And is that to with the reeds…

JLD: Well, I thought it had something to do with the reeds but I think it’s just because the bittern can hide in the reeds. But I thought maybe that kind of thing that David [Prior] and Francis [Crow] did [Organ of Corti (2010-11) by Liminal] through an acoustic feature [i.e. sonic crystals], as sound hits as a especially as that high-frequency hits, it actually bounces back again and bends round. And different frequencies behave in different ways, so...

AO: So are bitterns high or low frequencies?

JLD: Well, low frequencies would cope better because they’re much more bendy. Higher frequencies are more like, they go off at the angle of reflection. [makes low sound: DOOMP] off it goes again. There was this amazing documentary on telly years ago where this blind guy who’s learned to click really precisely, and he had objects on a table. And he’s going [chk chk chk chk sound] like there’s a cylindrical object there and an egg-shaped object there, and he’s just got to walk around it and go “chk chk chk” and it’s a very precise tick that he did.

AO: That’s amazing. When I used to work as a gardener we used to have to, we had a little hammer for tapping flowerpots to see if they needed watering. It made a different sound if it needed watering. So where should we go? What do you need for recording? We could skirt around the edge and…

JLD: Just nice to walk and talk. [Both inaudible for a bit] I didn’t bring my wellies.... Do people think of those projects with multiple voices, I don’t know much about poetry, but obvious references like Under Milk Wood [radio drama by poet Dylan Thomas, 1954]?

AO: Yes, that one is often brought up and I love that poem.

JLD: It makes a great radio piece.

AO: Yes, but to me it’s much more from thinking very hard about the oral tradition and Homer. I think always wanted to find what it is in Homer, a freshness that written poetry didn’t really have. And it felt that it really wasn’t composed by one person. That is, it had an accumulation of voices. And trying to recover that idea that a poem isn’t just one author, because if you have one author, it becomes very particular and quite stiff and it’s really of the world but if you have lots of voices and you have spaces between voices that allow sort of freedom space....

[Inaudible. Talk about where to walk next.]

AO: Like crowds, when you look at the reeds you see something thin and think what it will do to sound, but when I look at them, I think of crowds. I just love the feeling of the noise reeds make, it is a crowd noise. You love wind, yeah. You don’t need much. But there are other birds that live in reeds, like reed warblers they don’t have a low frequency. They must be using them in a different way.

JLD: The bitterns are interesting. I read recently that they use their esophagus to make the sound, rather than a syrinx. Cause I was wondering how they do it because there’s a similar bird, like a parrot that does a similar thing, called a kakapo which is a flightless parrot. So, cause can’t fly, it has to, basically with an inbuilt knowledge of acoustics – birds are good acousticians – so a kakapo actually makes a kind of bowl nest. The male kakapo in its lek makes a very pristine bowl shape in the ground which it is always cleaning. It chooses a location that might be beside the back of a tree so the sound will bounce off the back of the tree to reflect forward. And then they make this very low-frequency call to the back side. Very similar to a bittern. I didn’t really understand how bitterns were doing that but they’re inflating a different part of their body. Seems to be the esophagus, so the anatomy changes in springtime so they can make this sound.

AO: It’s interesting when sound and digestion occupy the same place.

JLD: That’s the breath as well, but it’s so noisy it’s a stupid place to put the voice box. And then when I clear my throat, which I tend to do a lot, it is full of signification, which is really unfair when all I want to do is clear my throat.

AO: I like that though, the clicks and coughs that the body makes underneath the [inaudible].... The moon is completely full. When I woke this morning, it was just going down. Really red moon. Very full and this is why there is a very high tide. It’s close to the equinox isn’t it?... I’m interested in the difference between the land birds' and the water birds' song. It’s like water birds just kind of shriek and sing a song full of grief and the land birds are twittery and cheerful.

JLD: It’s probably just acoustics really. These land birds can get high up. They can communicate from really get great positions. ...But if you are low down, like the bittern’s low-frequency call, they travel much further along water. That’s called the “foghorn effect,” the way the sound can travel vast distances along the surface of the water.

AO: Water is very good with sound. So, you must spend a lot of your time naturally thinking about birds if you are an acoustician?

JLD: Yes and no. I remember Tony Whitehead [ornithologist and soundscape recorder based in Devon] telling me about a very common bird like a crow and it flaps its wings, you know, sort of flapping its wings. I made some comments saying, it’s giving off noises and Tony said no, that’s communicating. Every sound it makes is communication.

AO: When I was going to write about ravens and all the different ways they communicate—a lot of it is wing flaps and clicks.

JLD: I had an interesting problem with my larynx. It was a bit scary. I was at the tail end of a cold and my larynx had a kind of a spasm a couple of times, which meant I couldn’t breathe. It was quite a scary moment. It just closed.

AO: Like asthma?

JLD: That’s what the doctor said, but this is actually the larynx. Not my lungs but my larynx.

AO: Like your throat was closing up?

JLD: Yes, the larynx would just close. Involuntarily. I could breathe out, but I couldn’t breathe in. Maybe for about fifty seconds.

AO: It’s not something you can treat?

JLD: Luckily it hasn’t happened for a while now. I think it may have been virally related. I find it interesting that the voice box could kill you. If the voice box closes down, it just closes. You can’t breathe. That’s a bit stupid.

AO: Well, but that’s interesting because I noticed that when I was doing Memorial in the South Bank – an hour and a quarter – from heart and was quite nervous that I might forget it. I just became so aware of my breathing that every time when I was speaking, I couldn’t breathe and I just became interested in... why poems are punctuated as they are, it shows you where to breathe, the voice is the stopping of the breath, particularly consonants.

JLD: I certainly think about breathing when I’m composing. Probably comes from playing the violin, you think of a bow length, and a bow length, and a bow length which is a breath. It’s like an inhale, exhale. Down bow, up bow.

AO: I was taking really deep breaths when I was performing, you know, because I’d get through a paragraph section and I’d try to do it all in one breath and then just breathe, or very short breaths.

JLD: This might be a silly question, but did you get any training or guidance?

AO: Not really, no. My brother’s an actor and I talked to him after that. And the thing that really interested me that he said is that the human mind works in three-second snatches. You re-think something every three seconds.

JLD: I think William James said something like that – the specious present.

AO: Anyway he was saying that when he’s acting, he uses that. He breathes and re-thinks every three seconds and I find that really helpful because it measures about half a line. And so, whereas previously I was thinking how I’d get through a whole 12 lines text.

JLD: Kind of a big gulp.

AO: If you break it up and imagine yourself recomposing every three seconds…

JLD: So, you’d have had to have learnt it that way.

AO: No, no, I learnt it in longer sections but then if I’m re-articulating it, I make myself hesitate every three seconds.

JLD: I’ve been listening to the CD [of Memorial] and you rapidly produce quite a mesmeric effect for me as a listener.

AO: I’m really torn by that because people often say after reading that, they went into a kind of trance. But in a way, I’m much more interested in poetry waking people up.

JLD: In Dart you definitely go BANG. Suddenly something happens and BANG we’re in another situation now and the energy is completely different.

AO: I mean there should be that effect in Memorial because it’s a series of different people, but I suppose it’s always an authorial voice in a sense.

JLD: There are pitch qualities to your voice and maybe the recordings emphasize it less than live performance. You know you could take one of those recordings and kind of see the pitch contour of the whole thing. It’d be interesting to do, to see if there’s a consistency to it.... Maybe you wouldn’t want to do that. Now the tools exist where you can analyze it very quickly and get a sense of…

AO: I normally hit quite low when I’m sort of controlling it, but if I get into it, I’ll go higher, I think... There’s a big difference in where you and I work. I’m very interested in memory. And, er...

JLD: I’m terrified of memory.

AO: Yeah, well you see, I’m terrified of it too but I think that’s what I like about it. Before I went the South Bank to perform, I just had my book and an oyster shell and I thought, either I’ll take the book in or I’ll take the oyster shell in and I knew if I took the book in I’d be so timid I would refer to it. But if I didn’t have it, it’d be like jumping off a rock in cold water. You just have to do it! But I think that edge of fear, I really like hearing that in a poet. I like the fact that it’s there and it matters, and you might do it wrong.

JLD: Be like “Oh shit!” Can I say it like that?

AO: Or just having to spontaneously compose if you do do it.

JLD: You must get people sitting there with the texts in their hand.

AO: Oh, it really annoys me. At the very end of that performance, I noticed there was actually someone with a little torch in the audience. Completely threw me.

JLD: Do you know Ursonate, the famous sound poetry piece by Kurt Schwitters from the 1930s. It’s an extraordinary piece. It’s got this very fast...it’s all phonetically based, German phonetically based nonsense and rhythms and stuff.... This must be a quarry, I guess.

AO: Yes. There are a lot of lime quarries around here.

JLD: I’ll send you my paper on sound walks [Soundwalking: Aural Excursions into the Everyday (Ashgate, 2009)]. It’s kind of a historical paper so it’s not my take. I did my best. It’s really for teaching but it’ll give a sense that there’s a tradition and different influences and...

AO: I’ve always found the walk quite a difficult form. I’ve always liked the idea of writing a piece that is simply a walk. Because at first, language is quite photographic it tends to, at any rate, mine does, it tends to work in flashes of stillness and then jumps to the next one. And it’s quite hard, partly because of the rhythms I use. I’ve always been very against flowing rhythms, like particularly against the iambic pentameter, the main rhythm English poetry has worked in.

JLD: That Peter’s [Peter Oswald] territory.

AO: Well, maybe that’s why. So, I’ve been much more interested in the rhythms that jolt and jar and that makes it quite hard to write a walking poem because I don’t have anything kind of fluid and flowing in my repertoire.

JLD: The big pieces are very flowing.

AO: Well, they are.

JLD: There’s maybe like a piece of music you could...you could have a different level of perspective. There’s a larger scale.

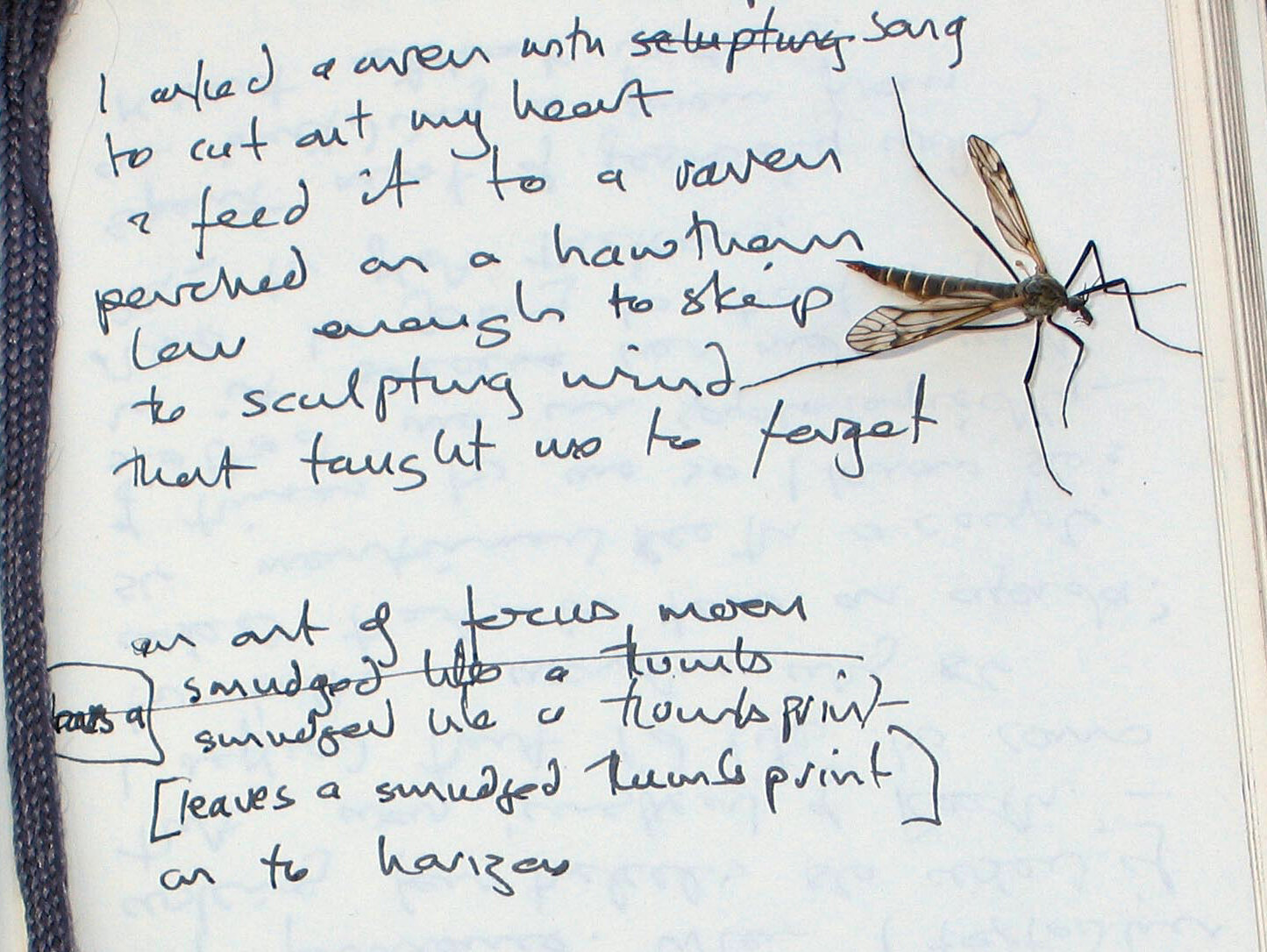

AO: In a way I think Memorial is the most even of them all, it’s got a monotony in it that responds to walking. But something like Dart is much more danced, really. So, it’s much more jagged.... But I composed a lot of Memorial while walking. I would, I’d basically copy out the Greek on a bit of paper and walk with it until, until I felt I could really see not just the words but what the words were looking at. And then I’d sort of write while I was walking.

JLD: But did you stop and start?

AO: I’d have a little notebook and I’d sort of, I’d walk, and if I thought there was something I needed to remember, I’d jot it down. And then also, when I was learning a poem, I would do that on that particular walk. It’s very much for me, that the tracks around here are embedded into that poem.

JLD: Would you want to tell people that, or?

AO: I wouldn’t keep it from people.

JLD: I’m wondering if you would end up with people doing a kind of heritage trail and this is the point where various characters got killed…

AO: That would be disgusting! [laughing] All these Greek epic characters on a Devon lane.

JLD: Well, the level of interest in the work is pretty high. Well it’s kind of fetishistic…

AO: But a walk is a kind of prose rhythm and I think the iambic pentameter is halfway between poetry and prose. And it is a walking rhythm; it’s got that footstep in it.

JLD: There is a great book by Jean-François Augoyard called Step By Step [Pas à Pas: Essai sur le cheminement quotidien en milieu urbain (Éditions du Seuil, 1979)] where he’s interested in... have you come across Michel de Certeau who talks about walking as a kind of speech act. And Augoyard, he’s actually taken it from Augoyard who goes into tremendous detail about all the linguistic acts that go into walking.

AO: Really? Like what?

JLD: That’s a good question. Like hyperbole. He’s kind of a semiotician and so it’s a way of kind of talking about, he’s interested in observing everyday people’s walking habits in cities.

AO: That’s fascinating. I can’t imagine how... so hyperbole would be a sort of walk like that?

JLD: Well, it’s how you talk about the walk. “We almost died…,” or something.

AO: Is it about walking itself, the physical act?

JLD: Yes, finding ways of walking as a speech act. I mean it’s classically French so it’s kind of ridiculous on one level, an attempt to take semiotics on quite an extreme level.

AO: You’re so widely read in this kind of obscure…

JLD: “Everybody knows about it.” He’s a great guy. I know him a bit.

AO: How do you know him?

JLD: He created a center in Grenoble called CRESSON which is about architecture and sound and sociology. He’s much more social science based than Schafer [R. Murray Schafer], though, his problem is, well he never translated the stuff. It’s always been in French. So everybody completely ignored it apart from a bunch of people taking PhDs in this part of France.

AO: I’d like to talk to you at some point about this project I want to do at Sharpham and get a community reading of Paradise Lost, probably take about 12 hours…