1 poem

“Nothing in evolution makes sense except in the light of phylogeny” (Notes)

One July, among the California redwoods, I watched a fire-colored salamander lumber over a log, and so my mind was ignited to meditate on shoulder girdles. Amphibians invented them.

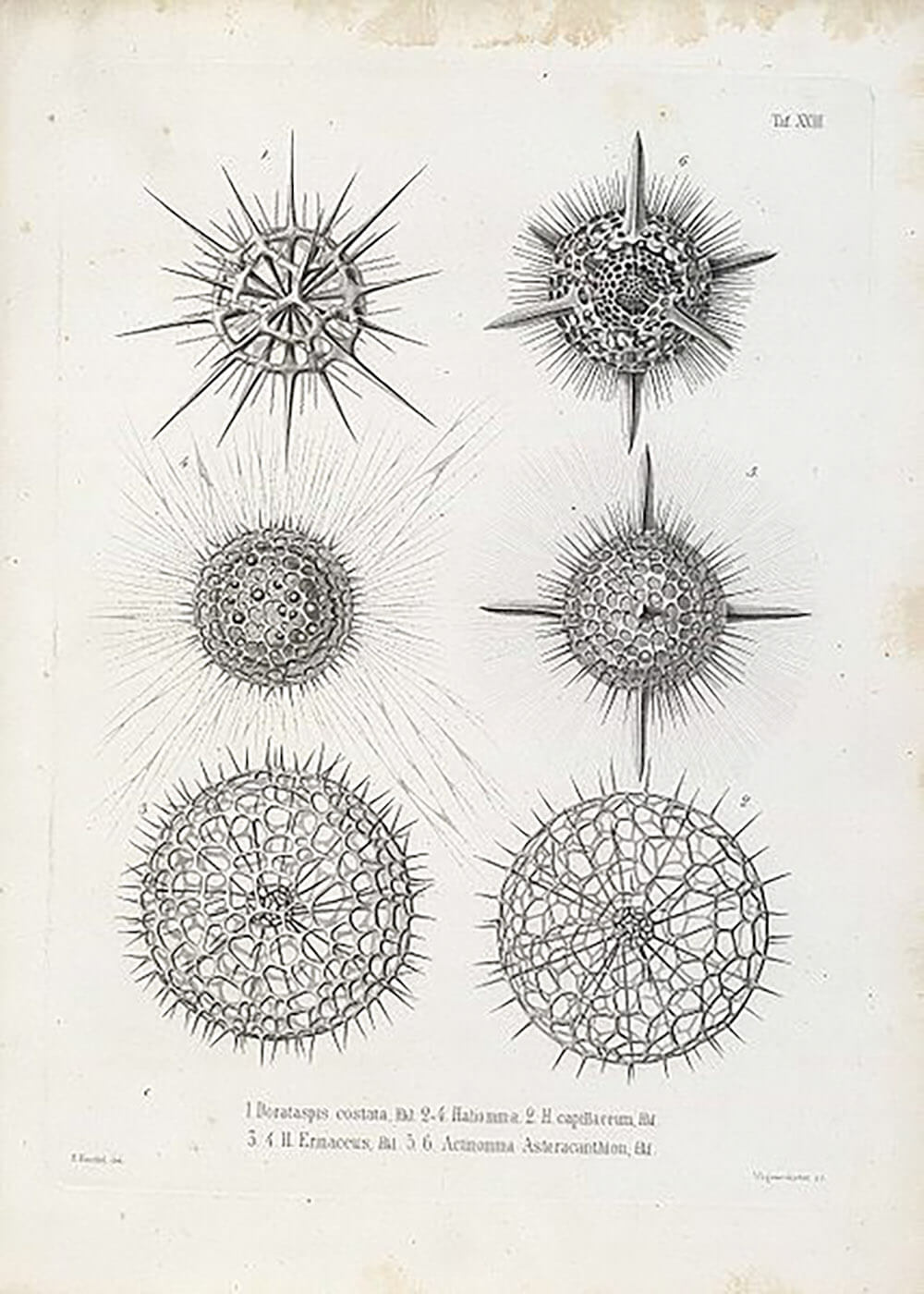

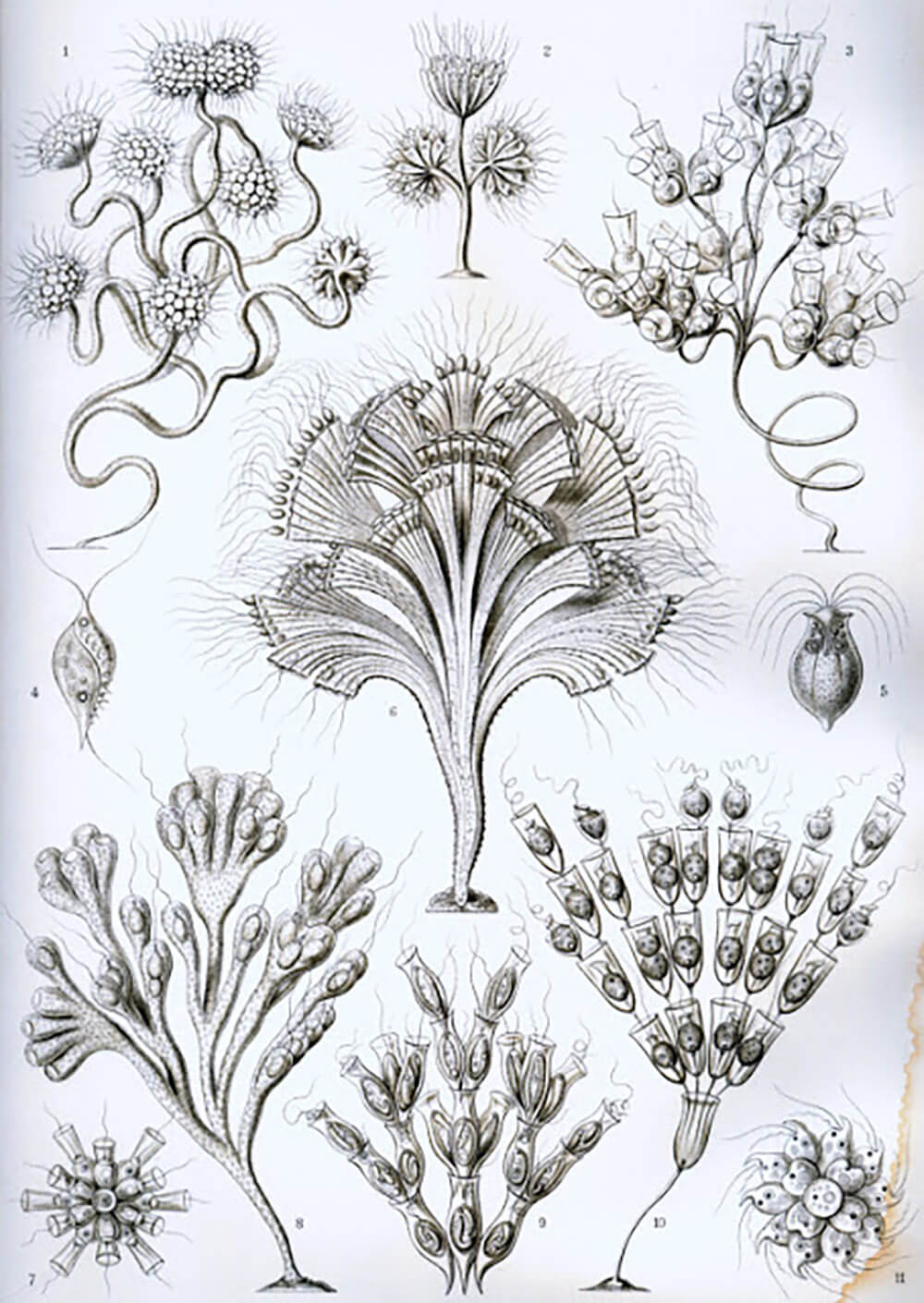

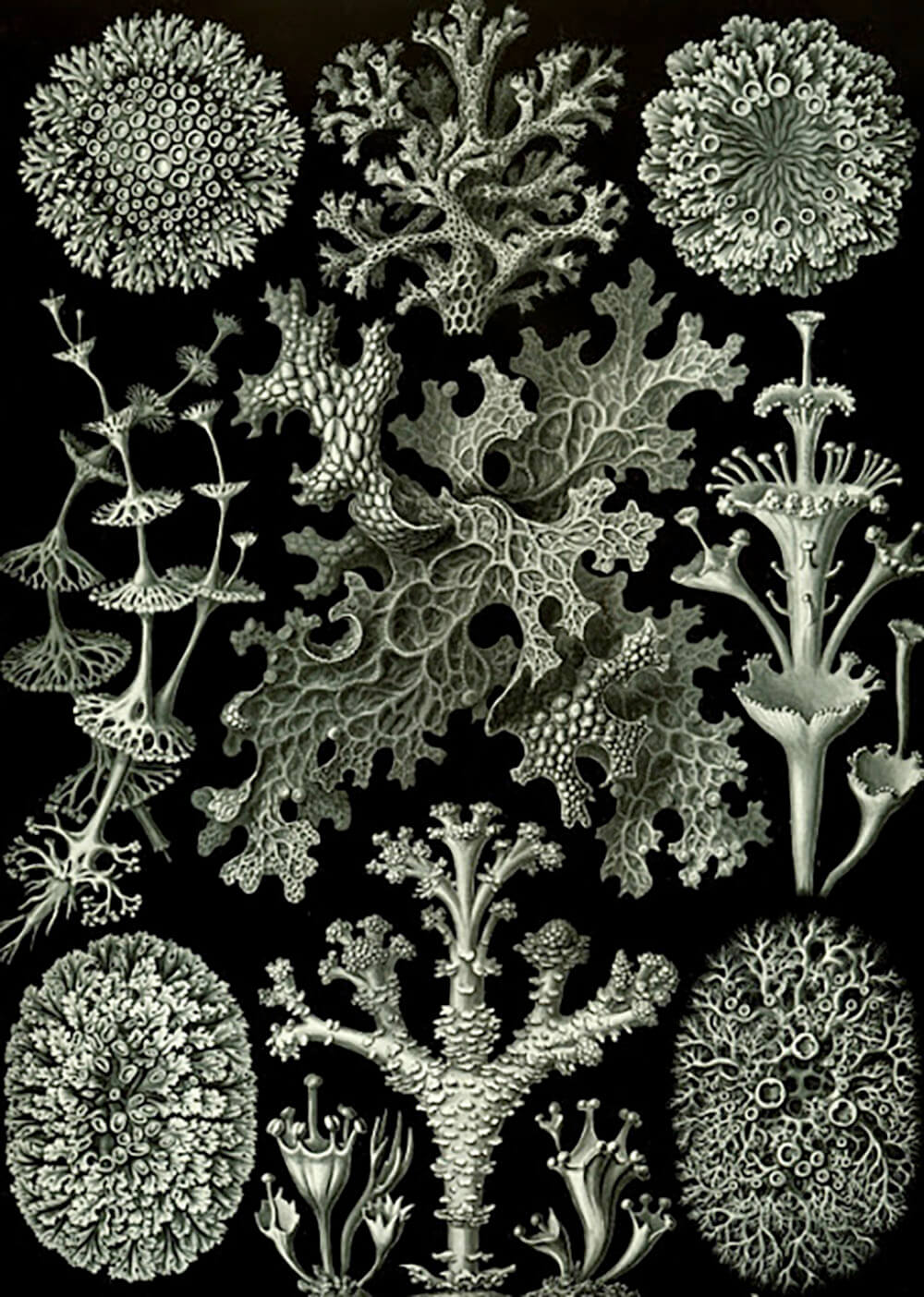

In the mid nineteenth century the German biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term phylogeny to contain the notion of the organismal lineages we all passed through. You too may have admired the drawings of diatoms, shells, jellyfish, radiolarians and spiders he sketched to describe life on earth :

phyla (φυλή):

tribe, stem, branch

geny (γεν):

born, birth

Phylogeny: all the plants who grew to be you. All the animals who did. I don’t mean because you were the telos causa, the reason or end-result, and I don’t mean because you ate them. I mean because they invented earth. Eventually they also invented you.

They twisted and turned and licked and hissed and allowed you to exist.

Phylogeny: a word I loved, was invented by a man who believed in eugenics (a word in turn invented by a man who invented the term “nature vs. nurture”).

eu (ευ): good, well

geny (γεν): birth, born.

Ecology, phylum, Protista

are also words first made in Haeckel’s mounding mouth.

Here I am at the bottom of Haeckel’s World-Riddle. Every word I utter haunted. In conflict with all the animals.

Can anything ever be held away from human tongues?

Some hunters, in ritual, sidewaysed the names

for bears (arktos, ursus), a

taboo on naming what is wild.

Instead of bear, a hunter said the brown one; honey-eater; good-calf; honey-pig.

As soon as a bear

crept out of a word, a word

did its work

to erase the bear.

The animals’ names light up in crackling flames.

Names mane & unmane.

Now we were rolling around on earth draping our tongues in Latin things.

We always said the bird doesn’t care what you call it.

That’s one way I’m different from a bird.

The bird takes flight from its word.

You share 70% percent of your DNA with zebrafish.

We all passed through roots and branches of the same tree, beginning somewhere with a few molecules combusting.

In the 60s biologist Lynn Margulis re-showed us symbiogenesis: we came about not only through competition but through cooperating. We carry evidence of species merger in our cells, and of species relation in almost every structure we daily rely upon.

Organismal lineages veering orgasmal.

One gene sliding into another one.

Is there one piece of you that doesn’t also, in some form, belong to someone else?

Your fingers ghosting chimp as they slender through air.

Organutan echo around the mouth.

Lobefin fishes did protolungs; acorn worms, something like a heart; amphibians, we’ve said, did shoulders. The more complex organs, like eyes, had to be developed many times, but jellyfish saw first, and not for us.

I live on Earth at present I don’t know what I am.

I seem to be a verb…

I swerve:

You know that science metaphors matter.

The physicist I sat next to at dinner in November1 was upset that the sound of two black holes colliding, captured

by “a pair of delicately positioned mirrors track[ing] the squeezing and stretching of space as gravitational waves go by”

was metaphored into an unsightly sound.

Black holes utter no thing heard by humans.

But now your ears hear beastish heavy breathing at your night door, a monster with a liquid heart monitor on. The deep water of dark space. This silent sound is ancient, and the energy it unleashed was 50 times greater than all observable stars.

[go to: sound of “black holes colliding”]

Margulis took issue with Darwin’s adopted tree image. No! she says, unless a tree has liquid, dripping, branches. But a net, yes, because everyone is and was sharing everything all the time, sliding intimate (genetic) materials between us, sucking off the same mouth of invention. It’s a man-made metaphor, and she can make a woman one.

My physicist says only math is not metaphoric. Language itself, which includes numbers, heaves to carry meaning from there (deep space) to here (you).

Biology, like language, is remembering. What life is is your cells remembering what other life did before it.

And even further.

Our cells recall ancient chemical joys and traumas, pre-life, while our limbs remember salamanders. A poem remembers our past in language and posits a future in the simplest sense, like a to-do note, hoping that it will be seen at some point hence and remind us of something worth feeling, knowing. It is an ecosystem that, like any functioning system, should deal with its own shit.

If we let phyla be taken over by its bedmate and homonym, phylla (leaves, petals, sprouts, sheaves, sheets of paper), we clear a silent space where we are all bound together and leafing from the same roots. If we take it further, to its homonymic neighbor, philo, we fall into love, with all our living friends, and with the dead left in traces

under oceans and in rivers and lake beds.

Eleni Sikelianos was born and grew up in California, and has lived in New York, Paris, Athens, Colorado, and Providence. She is the author of nine books of poetry and two hybrid memoir-verse-image-novels (The Book of Jon and You Animal Machine). Five of these have appeared in French and one in Greek, and her work has been translated into many other languages. Her writings, deeply influenced by ecopoetics and family as well as animal lineages, have been widely fêted and anthologized. Dedicated to the many ways poetry manifests in communities, she has taught workshops in public schools, homeless shelters, and prisons, and collaborated with musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists.