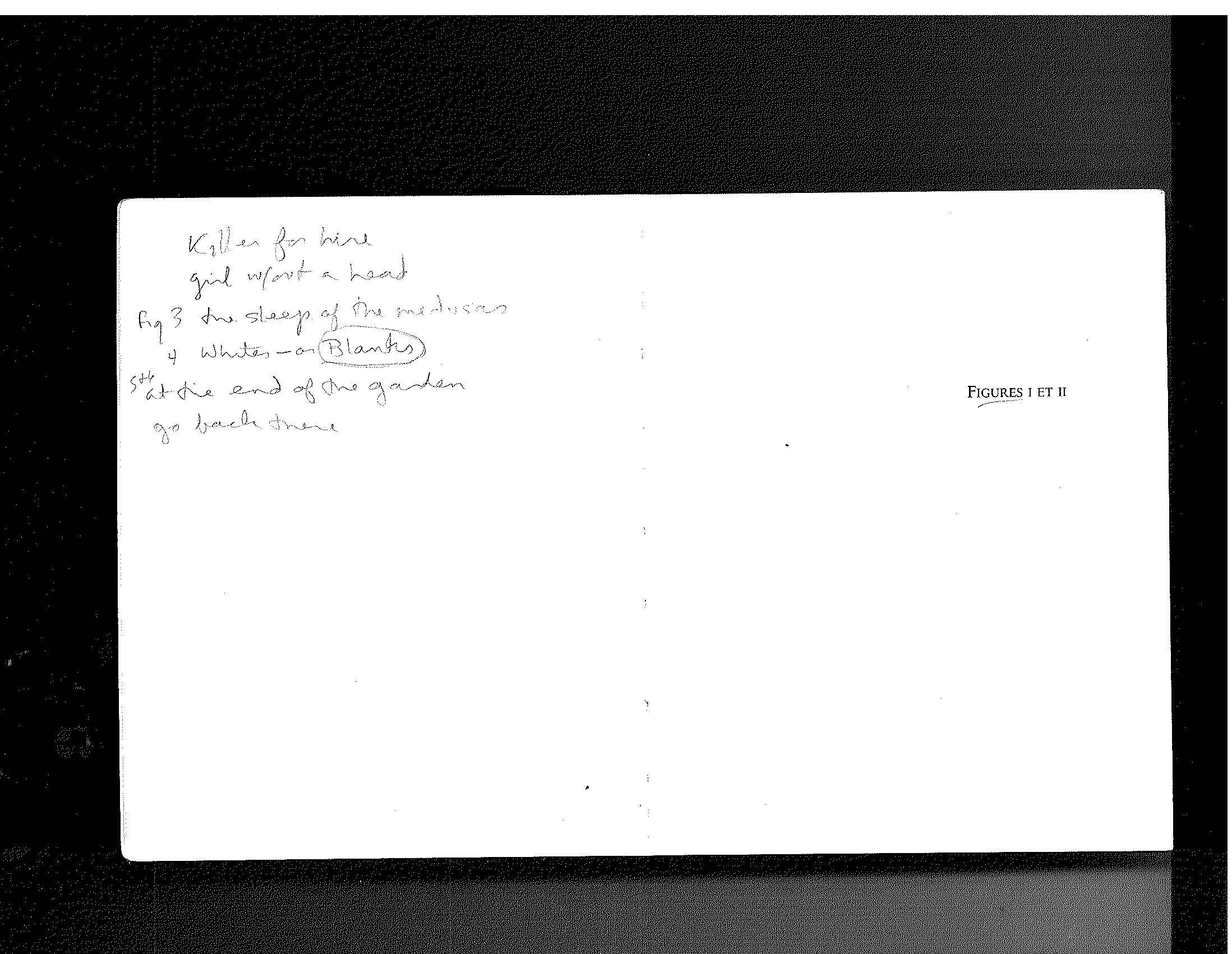

1 translation with notes

something happens

by Stephanie Chaillou (Editions Isabelle Sauvage, 2008)

Killer for hire

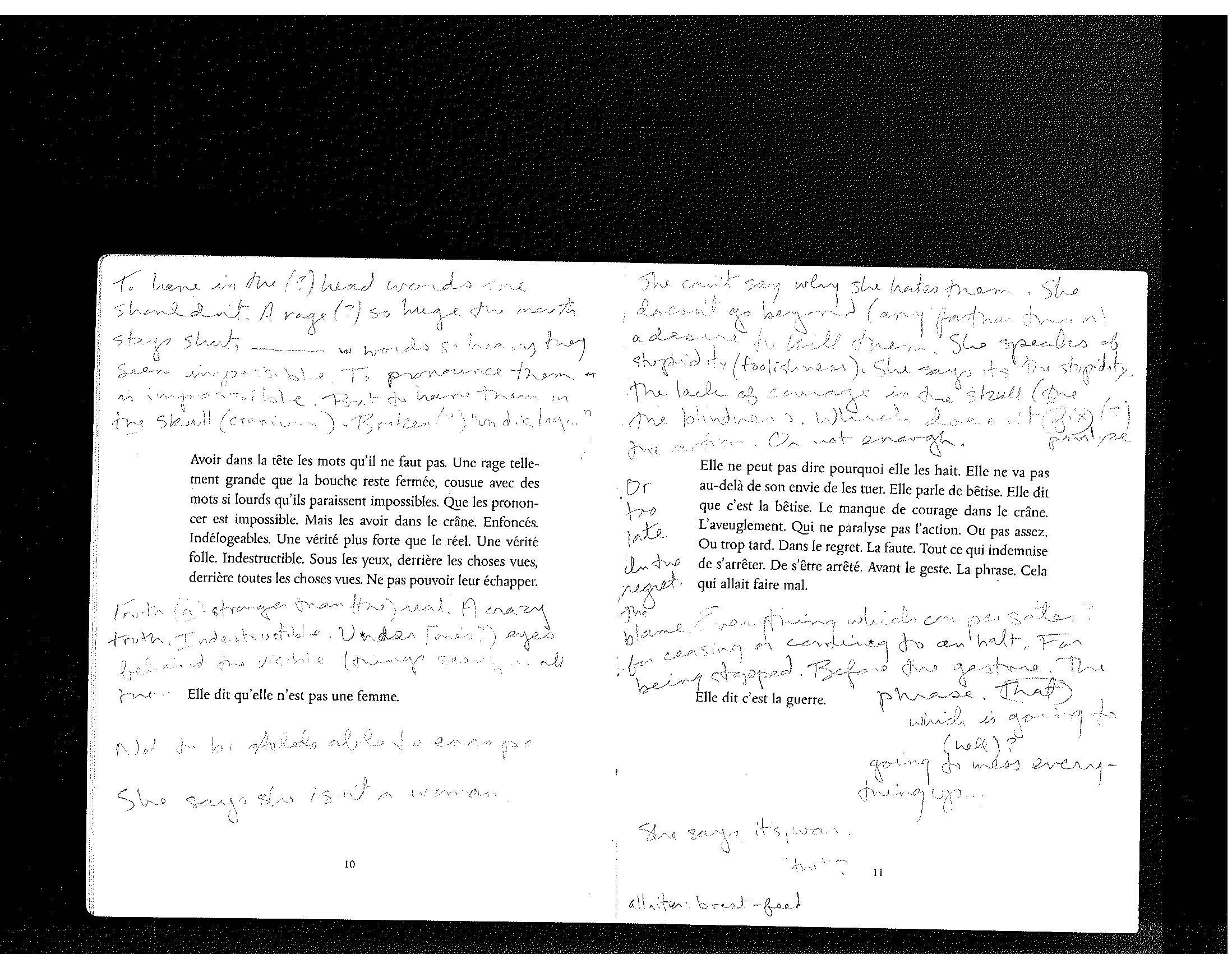

To have in the head words that must not. A fury so large the mouth stays shut, sewn with words so heavy they seem impossible. Impossible to pronounce. But to have them in the skull. Driven in. Fast. A truth stronger than the real. A crazy truth. Indestructible. Before the eyes, behind the things seen, behind all the things seen. Not to be able to escape them.

She says she is not a woman.

She can’t say why she hates them. She doesn’t go beyond her desire to kill them. She speaks of stupidity. The lack of courage in the skull. The blindness. Which doesn’t stop the action. Or not enough. Or too late. In regret. The blame. Everything that compensates for stopping yourself. For being stopped. Before the gesture. The phrase. Which was going to make it worse.

She says it’s war.

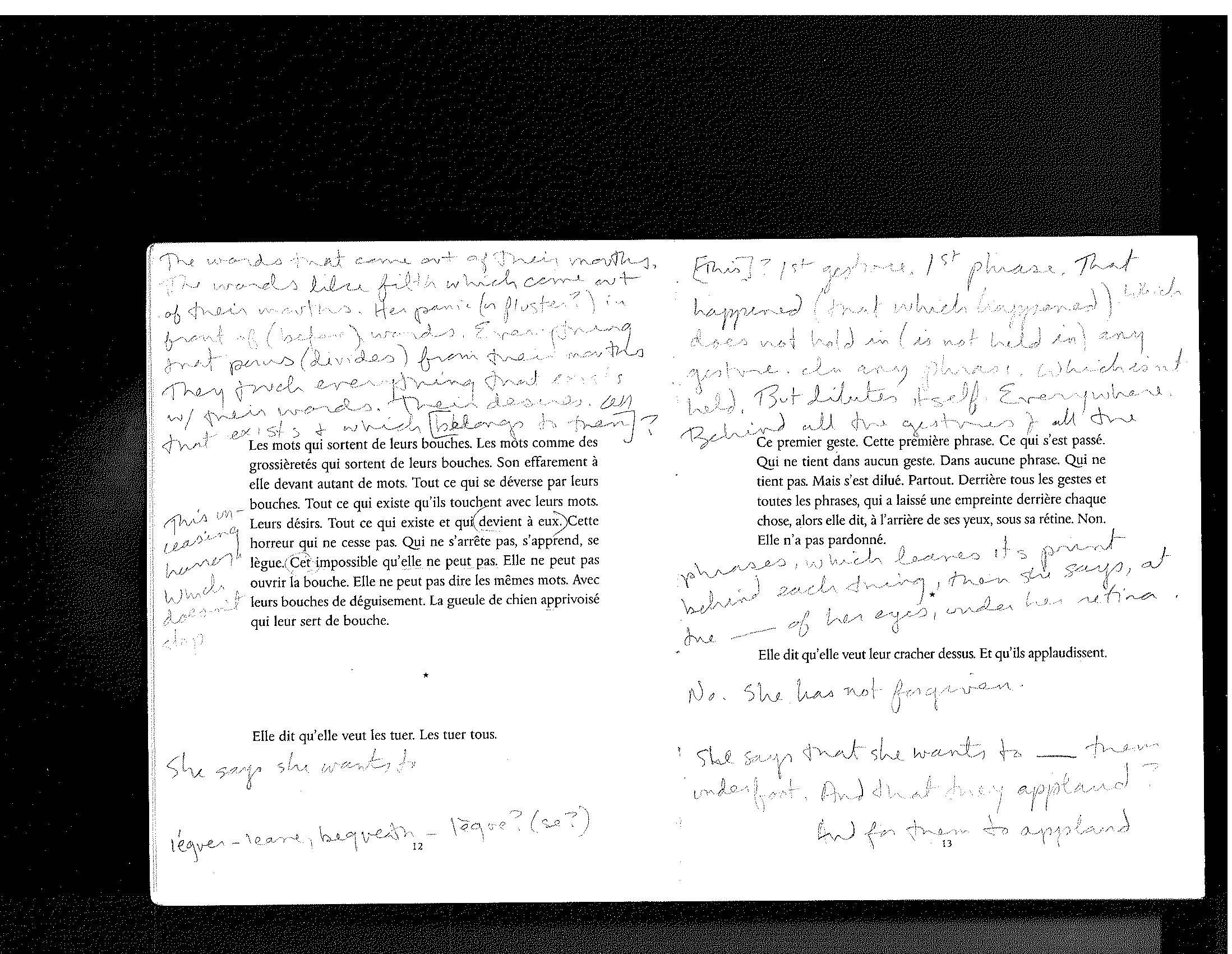

The words that come out of their mouths. The words like garbage tumbling out of their mouths. Her panic before so many words. Everything that pours from their mouths. Everything that exists they touch with their words. Their desires. All that exists and belongs to them. This unceasing horror. Which doesn’t stop itself, doesn’t know itself, doesn’t leave anything. This impossible she cannot. She cannot open her mouth. She cannot say the same words. With their disguised mouth. The muzzle of a tamed dog that serves as their mouth.

The first gesture. This first phrase. What happened. Which is not held in any gesture. In no phrase. Which is not contained. But dilutes itself. Everywhere. Behind all the gestures and all the phrases, which left its impression behind each thing, then she says, behind her eyes, under her retina. No. She hasn’t forgiven.

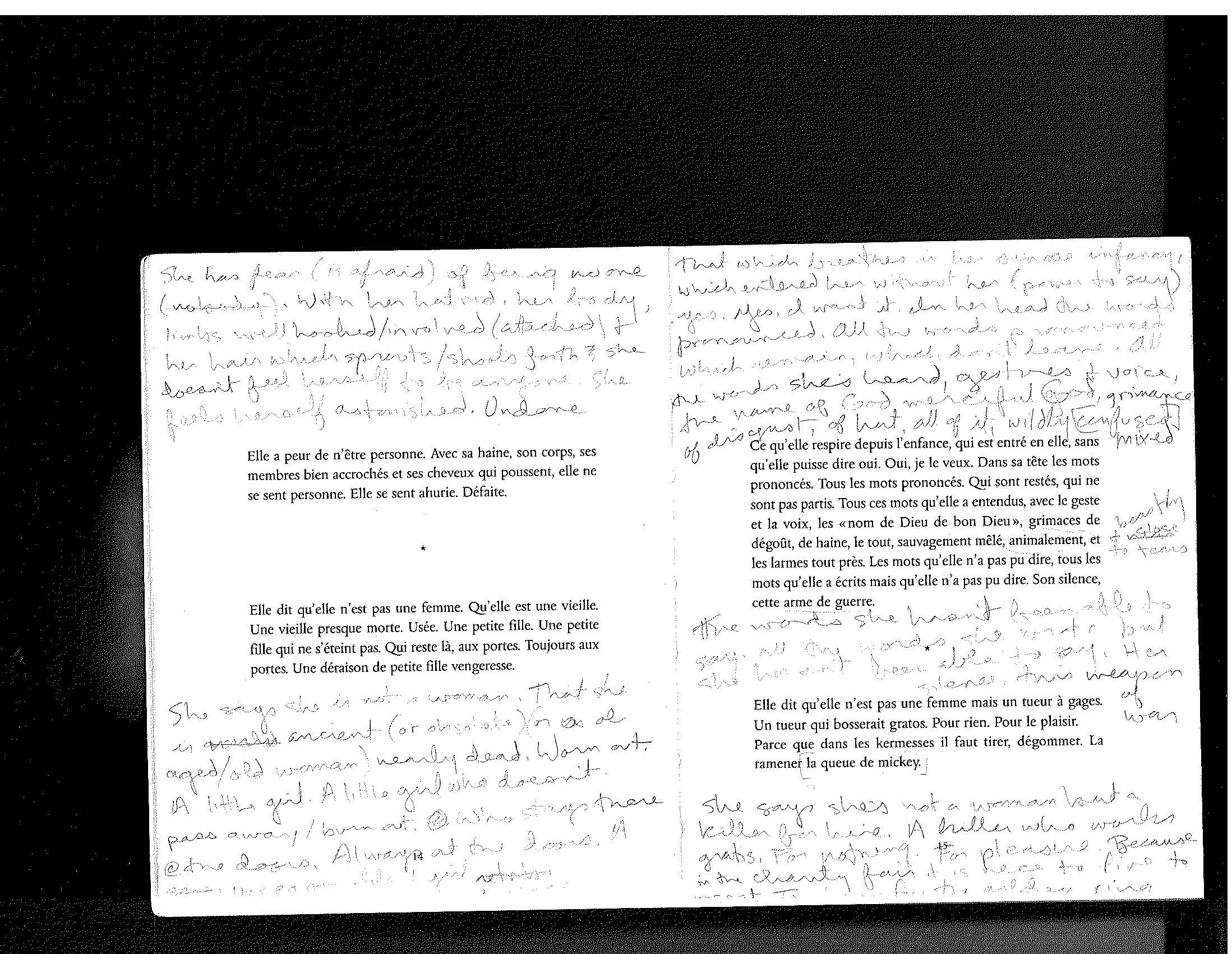

She’s afraid of being no one. With her hate, her body, her well-connected limbs, her growing hair, she feels herself to be no one. She feels dazed. Undone.

She says she is not a woman. She’s a crone. A crone nearly dead. Used up. A little girl. A little girl who doesn’t restrain herself. Who remains there, at the doors. Always at the doors. Foolishness of the vengeful little girl.

That which breathes in her since infancy, what entered her without her having the power to say yes. Yes I want it. Words pronounced in the head. All the words pronounced. Which remain, which aren’t leaving. All the words that she has heard, with the gesture and voice, those “name of God merciful God,” grimaces of disgust, of hate, everything, wildly mixed, beastly, and close to tears. The words she hasn’t been able to say, all the words she has written but can’t say. Her silence, this weapon of war.

She says she’s not a woman but a killer for hire. A killer who works for free. For nothing. For pleasure. Because at the charity fair it is necessary to shoot, to shove. To bring back the golden ring.

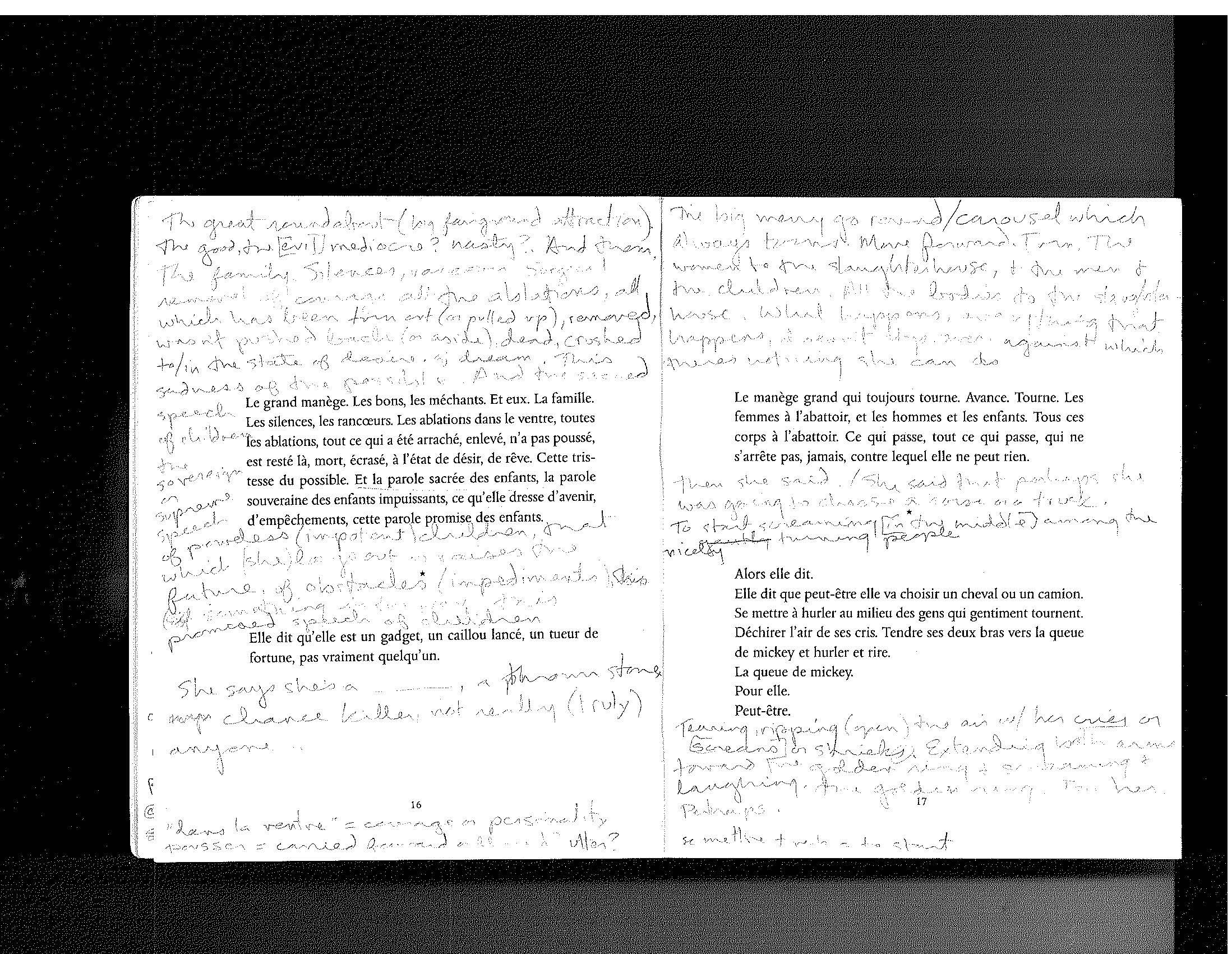

The big carousel. The good, the bad. And them. Family. Silences, rancors. Cuts to the gut, all the cuts, everything which has been torn out, excised, can’t grow, and remains there, dead, crushed to a state of desire, of dream. This sadness of the possible. And the sacred speech of children, the supreme speech of powerless children, which addresses a future, of impediments, this vow of the children.

The big carousel that always turns. Forward. Turn. The women in the slaughterhouse, and the men and the children. All the bodies in the slaughterhouse. What happens, everything that happens, which doesn’t ever stop, against which she can do nothing.

She said that perhaps she was going to choose a horse or a truck.

Beginning to scream in the midst of the people gently turning.

Rending the air with her cries. Holding her two arms toward the golden ring and screaming and laughing.

The golden ring.

For her.

Perhaps.

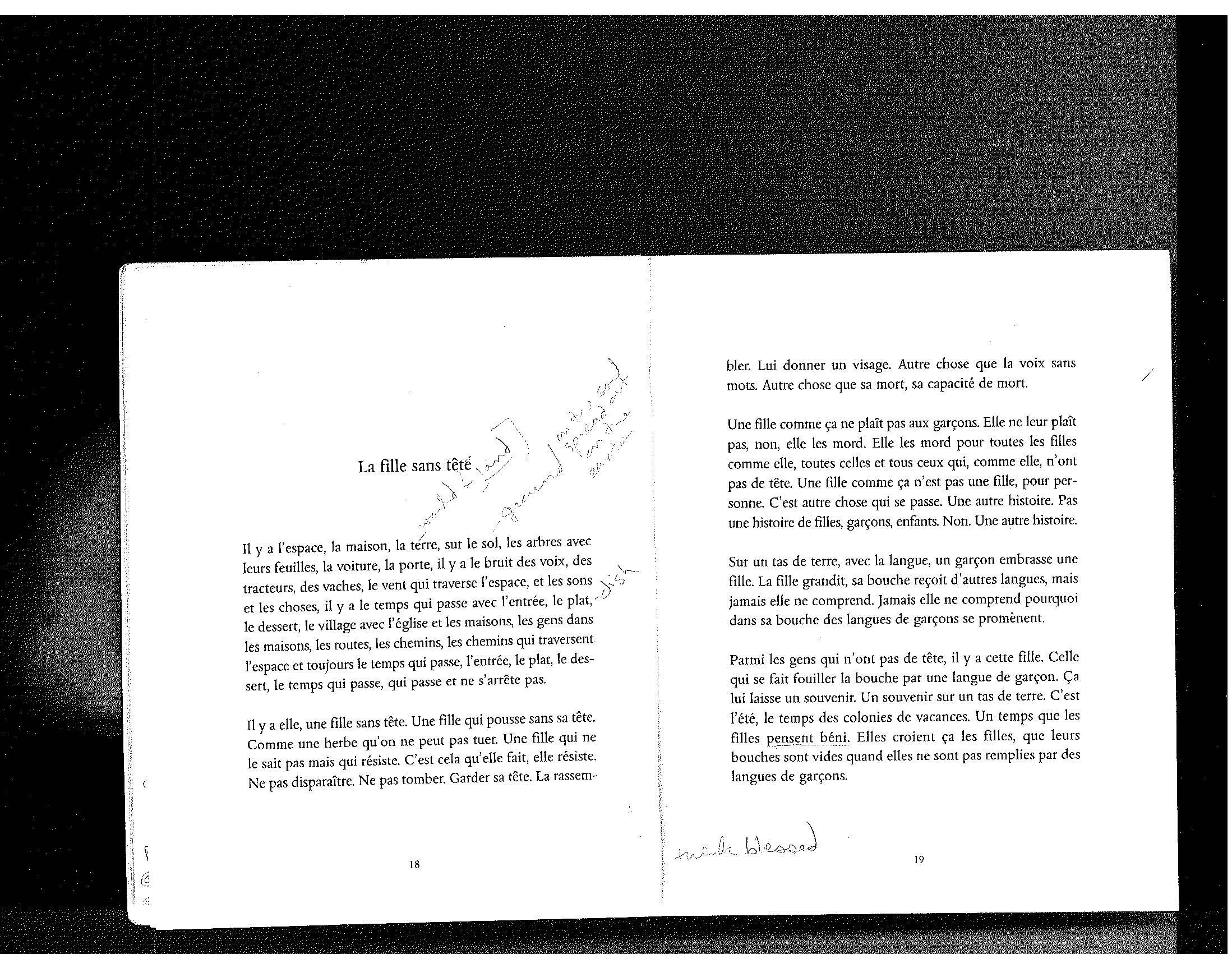

There is space, the house, the land, on the earth, trees with their leaves, the car, the door, there’s the noise of voices, tractors, cows, the wind which crosses space, and the sounds and things. There is the time that passes with the appetizer, the main course, the dessert, the village with its church and houses, the people in the houses, the tracks, the tracks crossing space and always the time that passes, the appetizer, the main course, the dessert, the time that passes, that passes and never stops.

She’s there, a headless girl. A girl who grows without her head. Like a weed you can’t kill. A girl who doesn’t know but who resists. That’s what she does, she resists. Doesn’t disappear. Doesn’t fall. Keeps her head. Pulls herself together. Gives herself a face. Something other than the voice without words. Something other than her death, her capacity for death.

A girl like this isn’t the boys what the boys want. She doesn’t please them, no, she bites them. She bites them for all the girls like her, all of them and all those who, like her, have no head. A girl like that is not a girl, for anyone. It’s something else that happens. Another story. Not a story of girls, boys, children. No. A different story.

On a pile of dirt, with his tongue, a boy kisses a girl. The girl grows up, her mouth receives other tongues, but she doesn’t ever understand. She doesn’t ever understand why the tongues of the boys ride in her mouth.

Among the people who are headless, there’s this girl. She who gets her mouth searched by a boy’s tongue. Leaving her a memory. A memory on a pile of dirt. It’s summer, the time of vacation camps. A time the girls think blessed. They believe that, the girls, that their mouths are empty when they are not filled by the tongues of boys.

In the head of this headless girl resting caught on a wire and hanging nonchalant pink tongues sprinkled with white dots. They don’t do anything. They wait. Hung one by one by a pin from a wire, they hang limply. Useless.

They would have had that, the girls, a word which would have grown in them, like a desire, a wish, a promise from themselves to themselves for the future, for their body in the future, what they were going to do, what they were going to become. A word that would not be from mother or father, no, not a learned word, something else, a word that would be born from an unknown place, without a progenitor. A word that would have grown in their bodies when they slept as little girls, when they played in the dark, their fingers tangled in the synthetic blond hair of their dolls. They would have had that which would have grown in them and which they could no longer pull up, because it would have stuck, everywhere, to their eyes, their hands, to the interior even of their mouth, it would be stuck fast, inscribed, papered everywhere, like a skin, a salve which would have become a skin. Then nothing no one could change what would be, nothing no one could undo that which in the interior of the bodies of the girls would have grown and become them, totally them. In their body, something would have grown that they could no longer remove.

The headless girl. She has no head. Without a head she advances.

She recalls the young hens one sliced across the neck with an ax in the courtyard of the farm. The blood spurted, reddening the gravel path. The hen restless, restless. As if it could still cancel the gesture, the movement of the ax toward the block of wood, as if there was something still to do, to hope for, as if by quickness she could still in some way save herself. Then, everything stopped suddenly, the hen fell in the middle of the stones, her yellow body sinking against the ground, rigid, headless, only the neck wet with the blood that spurted.

The head of some headless girls sprouts from infancy, when they didn’t yet know their names or who would feed them. She grows in the dark, in the middle of shadows and sleep. In silence, with just that which is necessary not to die. It’s raining outside, the bed is warm, there are the arms of the dolls, their blond hair, the rain beating on the panes, there are the shut eyes of the synthetic dolls, the noise of the rain on the panes in the bed which stays warm.

In the head of this headless girl, women dancing at night at the edge of the beach. They pull off their clothes and dance nude, feet in the sand still damp with the ebbing tide. They lift their arms to heaven and their breasts sway from side to side. The moon lights the white flesh of their breasts jumping from one side to the other there’s this jumping of their breasts side to side and their buttocks that sway. There is no music, only the lapping of the waves that ebb, lapping of waves more and more distant revealing the bay, the widening extent of mud in the bay, all black under the water that withdraws and parts there, on the other side, toward the island, and from here one can no longer perceive anything.

In the head of this headless girl the bodies of abandoned women rest. Those who wander at night on the edge of the road. Those one sees sometimes in the rays of headlights, at the very edge, there where the light cuts across the night, the thickness of night. There where eyes squint to discern presence. They appear suddenly, white, their hair undone. They appear and there is in this vision so great a closeness, they are so near, that the chassis of a car is nothing, only the spinning car doesn’t break down on you, on your skin, the astonishment of their presence, the blow that you feel in your gut. The women of the roads, the women with long hair who walk at night at the edge of the interstate, very close to the cars, so close to the rush.

In the head of this headless girl jostling images of lost children, fingers clenched in the pockets of their winter clothes. Children with red hands who wait in the bus, it’s barely day, the sky appears over the white fields, day will come, the children wait, there’s no game to fill the time, nothing to fill in the knowledge held in the eyes of these children who wait.

Laura Mullen is the author of eight books and the Kenan Chair in the Humanities at Wake Forest University. Recent poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Together in a Sudden Strangeness, Posit, Bettering American Poetry, and Diagram. Her translation of Veronique Pittolo's Hero was published by Black Square Editions in 2019.

A graduate of philosophy (DEA and CAPES) at the Université Panthéon Sorbonne (Paris I), Stéphanie Chaillou was professor of philosophy from 1995 to 2002 and directed events at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

quelque chose se passe (2008) is her first of several books of poems with Editions Isabelle Sauvage; she has also published Précisément là, parfois, an artist’s book. Chaillou created the art that accompanies Joanna Mico’s texts in Hypotheses as well, published in 2004. In 2009, Chaillou published Un léger défaut d'articulation, selected in the Young talents selection, Fnac, 2010. Un homme incertain (Alma, 2015) was her first novel.