essay & images

Codetwin

Last week, I had an enlightening discussion with a (Black) graduate student I’m currently mentoring at an MFA program in Interdisciplinary Arts. We were, together and separate, speaking of the processes of codeswitching.

And then I said something I’ve never said before, had never theorized for myself in quite this way before: I don’t know how to speak of my own relationship to codeswitching because I don’t have an original for the code to switch from.

This, dear Reader and Viewer, brought tears to my eyes.

Let me explain.

I grew up in a world of language that I never could fully claim as my own. I was raised by a difficult, tyrannical, totemic father who was born in Nanjing, China in 1948, just before Communism took its hold of his mother country. He was raised in Taiwan but because he was raised by Chinese nationalists, doesn’t claim a Taiwanese identity.

We hold within us, my twin and, before he moved to Taiwan a decade and a half ago, my older brother, a handful of the Mandarin words my father spoke to us as children: Baba (father), chi fan le (come eat), lai (come), zouba (let’s go), and a few others.

We took Mandarin in high school, a language that had begun to be offered while we were attending school. My fraternal twin stepsisters, who had just moved to the States, did our Mandarin homework. We did their English assignments.

Aside from those handful of words from early childhood, Baba stopped speaking to us in Mandarin. He instead spoke to us in broken English. At times, that particular variety of English was so wedded to how Baba understood us that he had a hard time understanding a sentence (even if he technically understood what all the words meant) unless we, too, spoke in that structure.

Baba was incredibly controlling and restrictive. He would claim that his restrictions had to do with a deep love and worry for us to get in trouble—especially my twin and I since we were born and raised as girls, but I believe that was a rationalization for his controlling behavior. There were other ways, ways I won’t get into here, that demonstrated his complicity in other types of danger finding their way to us.

From the time I was 8 (and maybe younger, trauma has a way of cutting off memory at the root) until I left his house, my father was heavily involved in a Chinese theater group. They put on plays in the Chinese community, epics and contemporary dramas, and my father acted and produced the plays with his friend community. When he wasn’t rehearsing or performing, the group was having long dinners at Chinese restaurants followed by hours of karaoke at one or another’s living room. We were always forced to come along on these outings. And so, my childhood, a formative time in language acquisition, was spent in silence, watching and listening to my father and his friends (and their children) speak in a language that was foreign yet familiar. We would bring books with us. Baba would set up a little area for us in the corner of whatever room they had found to rehearse, most often an abandoned police station. At the restaurants, we sat at “the kids table,” but all of those kids knew Mandarin and they used it as a distancing device. It was often clear that they were mocking us, in one way or another.

Of course, the school we attended was an English speaking school, and although I come across as a person who is as fluent in American English as the next person, it’s my firm belief that my relationship to language and oral communication has been greatly impacted by the amount of time we spent in silence. Well, I should give a brief disclaimer. The hours that I spent watching my father and his friends speak and rehearse, watching their every shift in tonation and change in facial expression, my brother and sister were off playing with the other kids. I was the one who was teased—for my naivete and vulnerability, my eagerness and affection. It was easier, and more interesting, to be the watcher.

Most days in our adolescence and teenhood, if we weren’t with my father and his drama club, we were at home. Well, I was, because I spent my life handling trauma (or the risk of further trauma) by being as obedient as possible. Newsflash: It doesn’t work like you think. And so, my brother and sister pushed boundaries, defied Baba’s order, and thus, were more integrated socially than I ever was. Funny that it would be me to become a writer.

And so, because I never fully socially integrated into any framework, especially linguistically, it’s my sense that codeswitching isn’t quite the right term. I thought of a better term, recently.

Codetwin.

But, let me explain.

I am the only left-handed person in my family. It’s a consequence of being born a mirror twin, in which twins are born with mirroring features (it has something to do with how late the egg splits). I hated my handwriting. I preferred the elegant coiling shapes that my eldest stepsister (two of my stepsisters came to the States many years earlier than my twin stepsisters did) scratched onto her notebook paper. And so, surreptitiously, I studied every aspect of my stepsister’s physical practice of writing: which fingers held her pencil, the pressure one finger gave the pencil over the other, where her wrist fell (if it fell at all). She was right-handed, of course, so I had to do make some small adaptations.

In other words, I gave her handwriting on the page careful study, and twinned my own writing practice to hers. This wouldn’t be the only time that I would do this.

I exhibited a similar practice with language, phrasing, accent, writing.

Now, it’s important, faithful Reader, that you understand I didn’t plagiarize another’s writing style, but that others (in a variety of skills and practices) were anchors for me to study in order to find myself. As I grew more into myself, I learned how to make my own way. But, being a twin was how I first understood myself, and doubling is also how I continue to discover myself, again and again.

*

In February of 2021, we were still deep into quarantine and lockdown due to the dangers of COVID-19. Only a handful were able to get a hold of any COVID vaccine. I had been divorced for a year at that point, my divorce having become final a year prior, just as the world was shaken to its core. I was shaken to its core. I had deeply loved a person for seven years who turned out to be a fantasy, a mirage. I was unmoored, living in a house I could only associate with grief. I craved physical contact, connection that can only happen in the squishiness of close proximity.

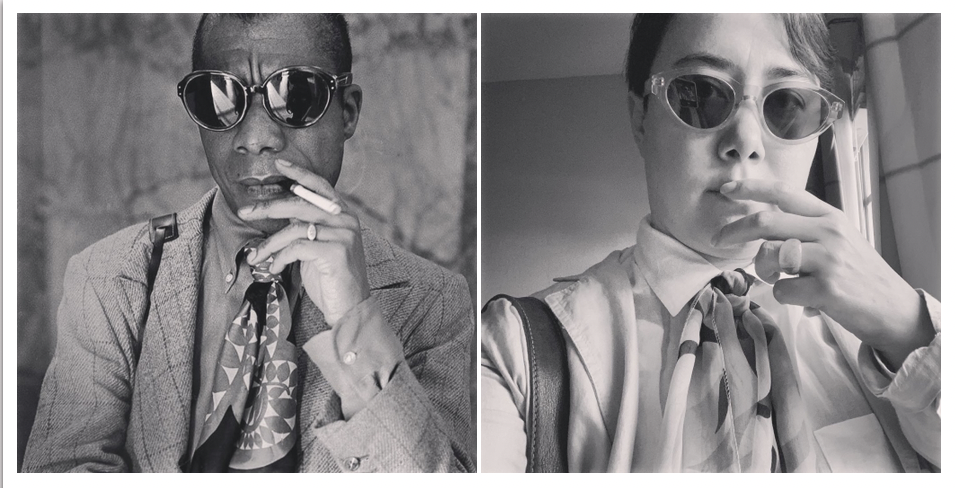

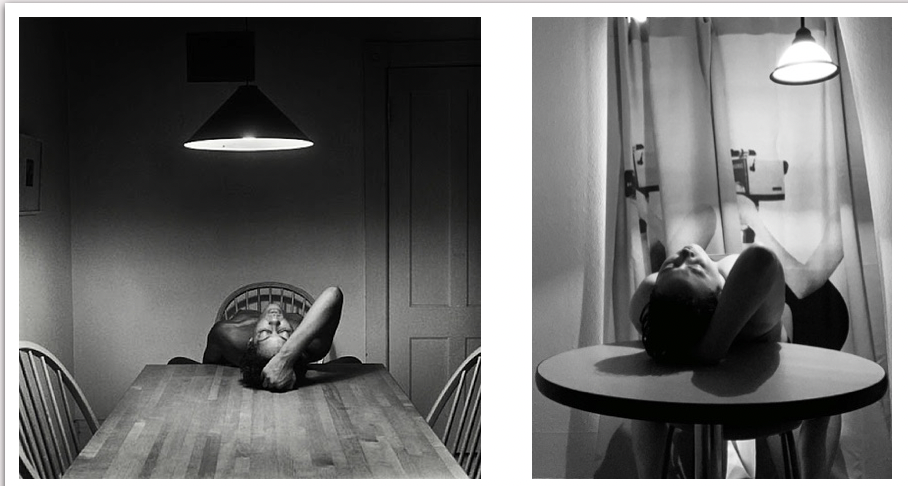

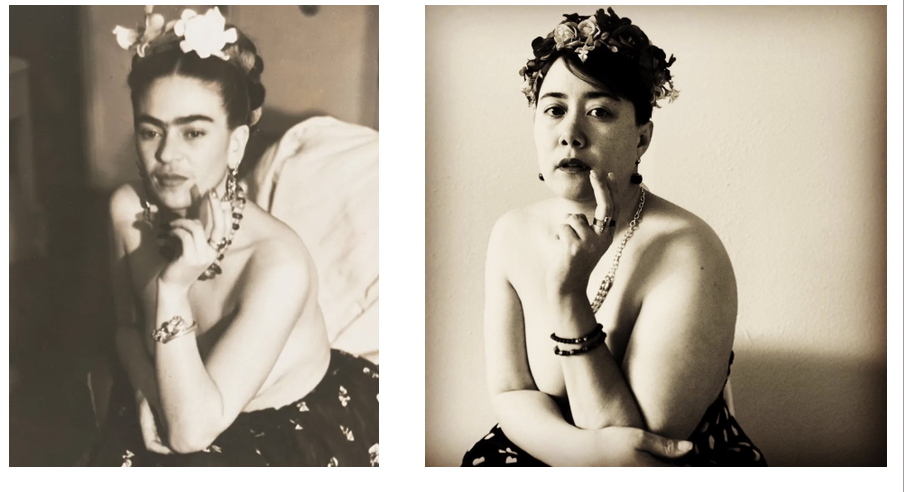

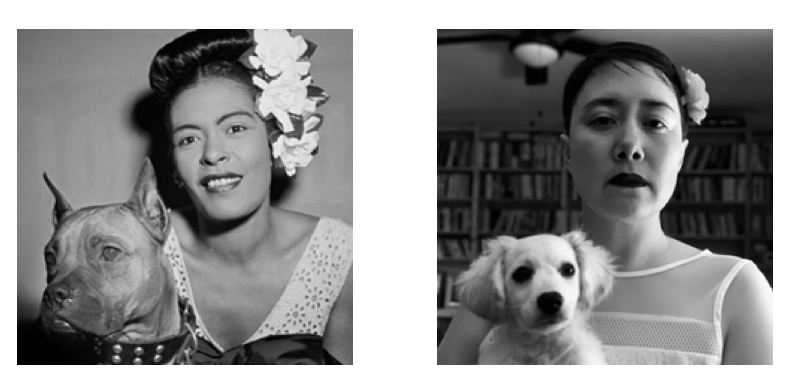

It started during Black History Month, quite organically.

I started playing with making self-portraits in which I “remade” myself into photographs taken of artists who had influenced my thinking, art-making, being in the world in some way. With only what I had in my closet, in the little limited space of my grief apartment.

Too grief-stricken to write, too dangerous to be outside of my apartment, it was a way to shift the interior while the interior was all we had. It enabled me to stay connected to my creative self in small ways, until the larger ways could happen, in my mind and my heart. And it was a way to give homage to those artists that have meant so much to me.

I made a remake every day of February.

And then I went into March and remade photos featuring women for Women’s History Month.

In April I made double-exposures of cover art from poetry collections for National Poetry Month.

On the heels of the murders in Atlanta, I celebrated Asian American artists for Asian Heritage Month.

Of course, June was pride.

In July, the Delta variant of COVID-19 began to impact the world, and I lost my steam. I had hoped to make these photos for a year. Now, I make them when it feels right, when I’m compelled.

*

A few rules, or parameters, made by no one but me.

With only two exceptions so far, I only remake photos of artists of color.

It felt an important framework to uplift the work of those who deserve to be centered after a lifetime of seeing the same white artists get remade again and again.

With also very few exceptions (sometimes props had to be bought), I don’t purchase clothing or accessories in order to make a photo that appeals to me.

Of course, in many of the images that I find or source, the artist of focus is wearing clothing and accoutrements that are much fancier than anything I could afford. I’m intrigued by the space between what I have in my closet and the (often) polished stylistic look of the original.

It’s not just the clothing that makes a particular image a contender.

Sometimes it’s the makeup, the gesture, the facial expression. In fact, some of the images I choose to remake aren’t “fashion” photos at all, but photos in which I see a particular aspect in a person that has had an immense influence on my life that’s reflected in the face, or the hand, or the body.

As much as one can be conscious of it, I try not to appropriate.

That means if an image includes a Black artist wearing hoop earrings, I don’t wear the same. I don’t choose African fabrics, etc. It feels important to take on the general structure and look of an ensemble and the shapes the face and body makes without “wearing” the cultural identity. To me, that would feel potentially harmful where I want to find joy and potentiality.

All genders allowed.

The remakes that excite me the most are the ones in which I’m taking on a gender depiction that is unusual, or unexpected, and how they’re received by the small group of followers that have been responding to the series. As a non-binary person who has felt increasing affirmation by embodying a traditionally-masculine look, I appreciate the exchange that happens when I take on a portrait by an iconic male artist.

Throw away the hierarchy.

I’ve chosen to focus on artists that are incredibly well-known in the mainstream as well as a musician I saw at a small venue in Tucson. It’s about the artist that has made some sort of impact on me and on the way I think through art-making, not the celebrity currency they happen to have with the American public.

*

As a twin, living in that liminal space between that of a “copy” and that of a singular fact remains a site of complication and conflict, but also renewal and rebirth. This series speaks to the power that comes for me in the codetwin, to learn the parameters and extensions of my body, subjecthood, and boundaries therein and beyond, by layering my own face, body, and manner of dress next to those who have had a role to play in my evolution as an artist, image-maker, writer, thinker.

Addie Tsai (any/all) is a queer nonbinary artist and writer of color. They collaborated with Dominic Walsh Dance Theater on Victor Frankenstein and Camille Claudel, among others. Addie holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Warren Wilson College and a PhD in Dance from Texas Woman’s University. She is the author of the queer Asian young adult novel Dear Twin. Unwieldy Creatures, their adult queer biracial retelling of Frankenstein, is forthcoming from Jaded Ibis Press in 2022. They are the Fiction Co-Editor at Anomaly, Staff Writer at Spectrum South, and Founding Editor & Editor in Chief at just femme & dandy.