essay

Spacewalking in the Archive: Transatlantic Black Feminist Lives

“The Black Arts Movement did result in the creation of Afro-American Studies as a concept, thus giving it a place in the university where one might engage in the reclamation of Afro-American history and culture and pass it on to others…Rather than having to view our world as subordinate to others, or rather than having to work as if we were hybrids, we can pursue ourselves as subjects.” Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory” (1987)

“Well into my 30s, I was far more knowledgeable about the literature and history of black America than I was about that of black Britain, where I was born and raised, or indeed of the Caribbean, where my parents are from. Black America has a hegemonic authority in the black diaspora because, marginalised though it has been within the US, it has a reach that no other black minority can match.” Gary Younge, “What Black America Means to Europe” (2020)

In June 2021, the Berliner Zeitung ran a story confirming that a city council in Berlin, Germany, had voted to rename part of one of its streets in an effort to honor the Harlem-born Black feminist lesbian poet Audre Lorde.[1]

This particular honor had followed more than a decade of decolonial activism in Germany that focused upon changing racist street names, such as those celebrating German colonialists, and having them renamed for notable Black anticolonial activists and artists. When I think about the famous litany that Lorde used to describe herself, “black, lesbian, feminist, mother, poet, warrior,” I don’t often think to add “American” to that list. And yet to my knowledge, no U.S. born person has been granted this particular honor in the wake of Germany’s recent reckoning with its colonial past.

Soon after I read this news article, I saw fit to post it in a Facebook group for Black Berliners that I’ve been a member of for several years now. The first day the post accrued a number of likes, but had no real engagement. The next day, however, one commenter wondered publicly: Were there no Afro-Germans – and here I believe they meant people of African descent reared in Germany rather than those who, like Lorde, had come to Berlin as intermittent exiles – were there no any actual Afro-Germans worthy of this recognition?

For a moment, let us suspend the question of whether Audre Lorde – Black, lesbian, feminist, mother, poet, warrior, American – is deserving of this honor; a honor that had previously been granted to the poet and activist May Aim in 2010, and the eighteenth-century philosopher Anton Wilhelm Amo just last year; as well as to Anna Mungunda, who on December 9, 1959, was killed by police in the Old Location massacre, sparking the fight of Namibian independence.[2] The question-behind-the-question of the commenter’s query – whether Lorde’s legacy had become an imperial one – was somewhat silly and somewhat profound.

Silly in that most people with a cursory awareness of Audre Lorde’s life and career are aware that her relationship to Berlin has become part of the mythos of the city, one that is especially resonant for the Black feminists who benefited from her diasporic mentorship, as well as for the successive generations of queer, activists, artists, and radicals of color who reside there today. Adding Audre-Lorde-Straße to the city’s lexicon of street names is a fitting commemoration of one of the midwives of contemporary Afro-German identity. To question whether there are other Afro-Germans more worthy of this honor is to also state quite plainly that there are other histories that we do not know and have yet to encounter. As inelegant as this provocation may be, it allows us to reflect upon how the canonization of activists and artists can inadvertently exert “hegemonic authority” over the stories we reclaim, both inside and outside of the academy.

Lorde is one such figure, a star with such a massive following that other historical and cultural narratives seem to orbit her, trapped in the gravity of her vital contributions to an array of intersecting movements and fields. Far from this being a singular event, we might also think of the rehabilitated figure of Marsha P. Johnson, whose participation in the Stonewall Riots, their work as co-founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries with Sylvia Rivera in 1970, as well as their motto to “pay it no mind”—the “it” referring no doubt to the prescriptive social norms that cross-cut her black, poor, and gender-nonconforming existence – all of these biographical details have posthumously turned her into an hallowed icon in the trans and queer community today.

And like Lorde, Johnson has also been recently honored through a renaming of public space: Williamsburg’s East River Park was renamed as Marsha P. Johnson Park last year.

Perhaps we should remain clear-eyed about these belated moments of recognition of Black queer and trans figures through the renaming of public space, however. A case could be made in both Brooklyn and Berlin that the memories of Lorde and Johnson have been enlisted by global capital to hide the violence of hyper-gentrification, to pinkwash away queer, trans, and houseless folk of color from the very public spaces being commemorated in their honor. Such contradictions illuminate the fractures of our society like broken pottery held together by gold resin.

Whether we receive these venerable acts with enthusiasm or with suspicion, I would caution us to make sure that all of our critical interest in and attention given to these particular subjects is not wholly subsumed in the spacetime of their particular existences. The term “spacetime,” taken from Michelle Wright’s 2015 book Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, aims to displace dominant and hegemonic origin stories of Blackness that begin with the horror of transatlantic slavery before progressing in a linear fashion outward. Understanding Blackness as a construct of space (a where) and time (a when), Wright’s work helps to destabilize the “slavery-to-freedom” narrative arc as the sole path to authentic Black identity formation. Complicating the wheres and whens of Blackness through our contemporary moment of archival retrieval – “the ‘now,’ through which the past, present, and future are always interpreted,” Wright’s framework allows us to “account all the multifarious dimensions of Blackness that exist in any one moment, or ‘now’—not ‘just’ class, gender, and sexuality, but all collective combinations imagined in that moment.”[3]

For theory’s sake, let’s consider the spacetime inhabited by one Black woman whose appearances and disappearances in the transnational archive complicates canonical understandings of diaspora and national identity. Performing a spacewalk, if you will, between the life she lived in Berlin in the 1940s, her death in Buffalo, New York less than a decade ago, and our contemporary moment of archival encounter continues a project of historical recovery begun by the Black women in Lorde’s poetry course at the Freie Universität nearly forty years ago, while also troubling the tether between freedom and citizenship for the African Atlantic subject in exile.

*

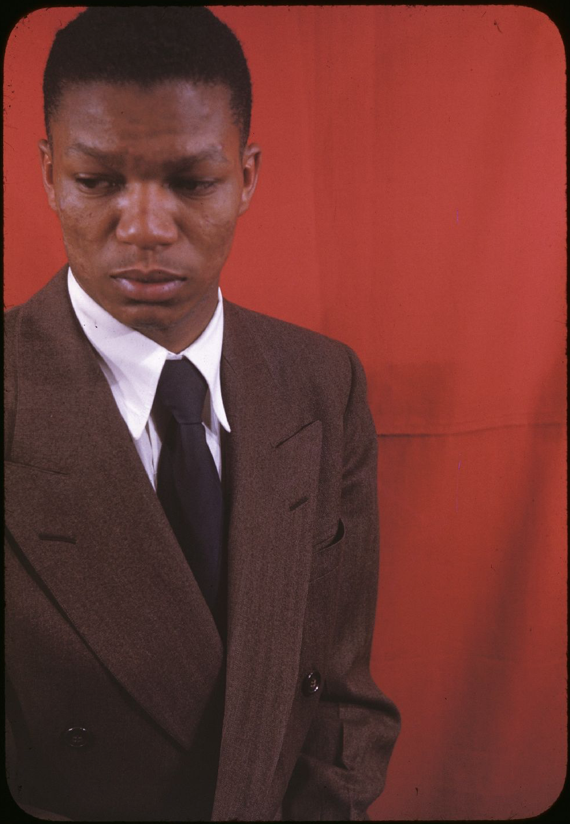

In September 1946, in Berlin, Germany, the African American writer William Gardner Smith interviewed a striking Black woman, a woman who “seemed out of place among the German blondes, brunettes, and redheads” frequenting one of the U.S. Army enlisted clubs in the occupied city. Smith served in the U.S. Army as an occupation soldier in postwar Germany. Alongside his everyday military duties he also worked a side hustle as a special correspondent to the Pittsburgh Courier, the Black newspaper made famous for its promotion of the Double V campaign during the war, a paper he had also worked at as a high school student before being drafted into the service. Smith’s assignment as a clerk-typist in Berlin gave him direct access to the former tools of his trade, and as a “special correspondent” to the Courier he wrote a slew of articles that detailed the injustices faced by black soldiers in Germany, the covert attempt to purge them from overseas service, and their reluctance to return to the United States.

But even among the many articles he wrote for the Courier’s readership back home in Philadelphia, this story was unique. Rather than offer another antiracist critique of US Army policy in Germany, Smith channeled his fascination with this tall and well-dressed Black woman into a feature-story.

“Here,” he wrote, “she stood out like an orchid in a field of gardenias; she was something rare, something to be sought after.”[4] The woman in question, identified in print as Madeline Guber Goodwin, had been born in Berlin, and her presence in Germany was, for Smith, was something of a mystery.

“So the American Negroes want to know about the German Negroes,” she said. “Very well. I will tell you what I can.”

Chatting in German, Goodwin told Smith that she worked in the city as an entertainer, and before the war she had traveled all over Europe. In fact, Goodwin came from a family of performers; her father emigrated from Togo in 1896 to take part in the "German Colonial Exhibition" at Treptow Park, Berlin. Decades later, during the Nazi regime, she performed in her family trapeze act “The Five Bosambos” in the Deutsche Afrika-Schau, an updated “human zoo” meant to showcase the benevolence of Germany’s colonial rule.[5]

After surviving World War II, Goodwin married an African American soldier during the occupation period, took his last name, and as soon as she was able, she planned to move with her husband and daughter to live in the United States. Taking a long drag from her cigarette, she told Smith bitterly, “I have learned to hate the Nazis.”

While African American GIs routinely described service in Germany as a “breath of freedom,” Goodwin made the decision—informed by her experience under Nazi rule—that she would rather immigrate to the United States than remain in Berlin.

Before the war, she estimated there were perhaps 2000 Afro-Germans in all of Germany, and most were, like herself, entertainers. “Negroes set the style in clothes for Germany,” Goodwin said. “Everyone followed their pattern of dress.” Her father was African and her mother was a white German, and Goodwin grew up as the youngest of five in her family, which lived in the neighborhood now known as Neukölln. Because there were so few Blacks in Germany, she said, her family lived well for at time. But once the Nazi regime came into power, all of this changed. “Life became very different. Once the Nazis brought their theories of racial superiority, things became bad. We were scorned as semi-apes. We were insulted on the streets. We could not work in the factories. Such a thing is crazy,” she said.

The point of no return for Goodwin involved one of her close girlfriends, also Afro-German, who had been sterilized by the state. Her friend had fallen in love with a white German man. The couple wanted to marry but were denied by the Nazi authorities. “Then,” she said, “one day the police came to her house and took the girl to a hospital. She was told by the medical authorities that it was feared she might bear a German child. But the child wouldn’t be an “Aryan.” So they performed an operation on her. Now she can never have a child.”

Because Goodwin’s father held French nationality, the American authorities gave her permission to marry an American soldier. “I think I’d like to go to America,” she said pensively, and Smith noted how her eyes ‘lit up’. “After so many years under the Nazis I think that would be a paradise. From the books I’ve read, and from what I’ve heard people say, everyone is treated exactly the same there, regardless of race.”

With that statement, Smith ended Goodwin’s profile bluntly: “She didn’t see me smile.” Smith treated her lack of knowledge of American racism with derision and dismissed her dreams of freedom in his own native land forthright. Yet he was so taken by Goodwin’s persona and experiences that he chose to interpolate her life story into his novel Last of the Conquerors in 1948.[6]

The thinly veiled portrait of his experiences as an African American soldier in a trucking company in occupied Berlin gained him great acclaim, and in recent years it has received renewed critical interest, especially from feminist historians of the German-American postwar military encounter.

Its protagonist, Hayes Dawkins, an African American soldier in Berlin, is told about the existence of Lela, an Afro-German dancer who worked in theater and clubs before the war. Like Madeleine Guber Goodwin, Lela was also waiting for her American soldier boyfriend to send for her to come to America. As Hayes’ girlfriend, Ilse, attests, “[Lela] was born in Berlin and then went to many countries in Europe to dance. She speaks so many languages, darling. You should hear her.”

“Negroes! I did not know they were here!” Hayes exclaims, with the same amazement that characterized Smith’s assessment of Goodwin’s uncanny presence in Germany, fracturing the author’s own “Middle Passage epistemology” that was loath to understand Black being & belonging as anything other than American, as anything other than a product of transatlantic slavery.

In the epilogue to my book Contagions of Empire, I offer a brief examination of William Gardner Smith’s tour of duty in Berlin, and argue that his witness – as subject and scribe of the overseas military apparatus – offered a counter history to America’s official military record of occupation. His communiqués and literary reflections of the American occupation still stand today as a singular record of the fervor of that disorienting and discomfiting moment for African American soldiers, reifying their experiences into protest and prose, and continuing a tradition of black military cultural critique that had been centuries in the making.[7]

As it stands, the contemporary historiography of African American military service has played a vital role documenting the black struggle for civil rights at home and abroad. In so doing, it has helpfully reimagined the black soldier as a black international, and has taken seriously the ways race, gender, sexuality, and citizenship have been negotiated within the contact zones of American militarism. Yet I would also suggest that the relative lack of critical inquiry into black military life overseas has fixated upon the freedom dreams of heterosexual men. In doing so, it has inadvertently trafficked in a heteronormative discourse of manhood rights, whereupon the demonstration of a particular form of masculinity (martial courage, for example) entitles the black male subject to rights and privileges of citizenship.[8]

All of this said, I must admit that, like Smith, I too am fascinated by the figure of Madeline Guber Goodwin. The rakish angle of her hat, positioned just-so atop her head; the fur-lined lapels of her embroidered coat; and the familiarity of her smile; her diasporic family history of colonial performance in the 1890s through to the 1930s; her personal witness to the sterilization of Black Germans during the Nazi regime – all of these things make Goodwin an incredibly alluring historical figure. To me, the Afro-German/African-American encounter as chronicled by Smith carried the possibility of anti-colonial & anti-racist solidarity within overlapping Western imperial archives, the kinds of encounters that have been known to occur in the contact zones of American militarism, a possibility of belonging forged in the ruins of occupied Berlin.

Smith’s European service ended on January 21, 1947, and he arrived in New York harbor on the S.S. Marine Robin on February 1. During his return voyage he took time to reflect upon the paradoxical feelings of freedom and constriction he experienced as an occupation soldier in Berlin, and began working on his novel in earnest soon after. The success of Last of the Conquerors paved the way for his own permanent emigration from the U.S. to France, where he lived for two decades before dying in Paris in 1974.

And what of the figure of Madeline Guber Goodwin, whose encounter with fascism in Germany gave her the conviction to expatriate? With the research assistance of Brigette Reiss and Kim Everett – two friends of mine in Berlin – I learned that Goodwin did in fact emigrate from Germany in 1947 to the U.S. on the USS General Muir, only a year and two weeks after her profile in the Pitsburgh Courier. With her child Hertisean in tow, she arrived in the port of New York on September 21, 1947.

What’s more, Brigette –who is a crackerjack genealogist – discovered that Smith’s transliteration of Madeline’s surname was incorrect. Instead of Guber, it was Garber. With that information, she was able to substantiate the claims Madeline made about her family, her birthplace, and her role as a member of the Five Bosambos in the Deutsche Afrika-Schau – complete with pay lists for the “Garber Geschwister,” the Garber siblings.

Madeline Goodwin moved to Buffalo with her husband Jack, and became a naturalized U.S. citizen. She remarried in 1958, and lived the rest of her very long life in Buffalo, dying in 2013 at the age of ninety-four.

Considering the archival traces of Madeline Garber’s life once again, I remain amazed by the radical possibilities and potentials of diasporic kinship produced in the wake of overlapping militarisms – that the creative use of difference can usefully destabilize our understandings of race, gender, and national origin. At the very least, Smith’s death in Paris and Goodwin’s in Buffalo necessarily complicates who and what we mean when we speak of “African American” in the aggregate, as an imagined community forged in the fire of chattel slavery and not, for example, through the kiln of colonialism. Swaths of Garber’s life intersect with canonical texts of Afro-German history, and here I’m thinking of the multi-authored Farbe bekennen (Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out), Robbie Aitken and Eve Rosenhaft’s Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diaspora Community, 1884–1960, Tina Campt’s Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, as well as Tiffany Florvil’s recent Mobilizing Black Germany: Afro-German Women and the Making of a Transnational Movement. I take issue with William Gardner Smith’s insinuation that Garber was naïve to believe she might have a better life for her family in the states. This doesn’t read as naivete to me; I see it as a courageous proposition, no doubt filled with risk. But she knew, better than most, what she was leaving. The fact that she decided to take her chance on life in the U.S. Jim Crow North only enriches what we might understand as the vicissitudes of the Black European experience; and once the whole of her story is told, her life may offer us additional models for understanding how African Atlantic feminist subjects negotiated race, gender, sexuality, and nation, in the long twentieth century marked by displacement, war, and migration.

*

I should note, here, that I was so captivated by Garber’s story I had planned to include it in my book, as the epilogue to the epilogue, if you will. Once Brigette located the phone number of a woman she believed to be Garber’s daughter, she urged me to follow through.

So I did. The conversation started sweetly enough. I introduced myself, and told her about my research. After confirming a few biographical details Brigette had stitched together I then mentioned I thought I had found an article about her mother in Berlin after the war.

For one reason or another – an attempt at transparency on my part – I read her the opening paragraph of Smith’s article. I hadn’t quite finished the third clause of the first sentence, where he remarked that Garber had “inhaled deeply on the last cigarette she had” that she stopped me dead in my tracks.

“No, no, no, no, no.” she said. “My mother hated cigarettes. She never touched them.”

In my mind I thought: It was 1946. Everybody smoked, and if they didn’t smoke cigarettes, they used them for currency. Still, recognizing I had crossed an invisible line in my attempted openness, I circled back to one of my original questions. “Ma’am, was your mother born in Berlin?”

“Yes!” she exclaimed, and added in an exasperated tone, “and so was I!”

At this point, recognizing my skills as an interviewer were lacking, I thanked the woman for her time, and asked her if I might send her the article so she could read it herself. She said that would be fine. An hour and a half later she sent me back a three word reply.

“Not my mother.”

The brevity of the refusal stung more than I could have expected. I didn’t care so much that Garber’s story wouldn’t make it into my book. Rather, it was as if Madeline Garber Goodwin had been free-floating in the spacetime of occupied Berlin, forgotten by most if not all, and here was a tether of living kinship who had, at the very last moment, refused her curtly, leaving her to walk in space alone again.

It made me incredibly sad. I called up my mother, who was waiting on the outcome of the call, and told her what happened.

“Well,” she said matter-of-factly, “Sometimes folks don’t want to be found.”

This truth, the very definition mother wit, embodies one of the tenets of Black feminist thought that those of us invested in chronicling the historical lives of Black women must continue to work through: the culture of dissemblance. Historian Darlene Clark Hine coined the term to define the behavior and attitudes of Black women that created the appearance of openness and disclosure but actually shielded the truth of their inner lives from their oppressors—making it difficult to find evidence of their inner lives and inner thoughts within the historical archive.

Some folks don’t want to be found. Over time, that has become easier for me to understand, and to even respect. But that doesn't mean we won’t stop looking. Even without a living tether, Madeline Garber Goodwin’s story destabilizes the when and where of Blackness in our present moment, complicating our own spacetimes with her witness and her will, and making us wonder how many other Black women in Germany found self-actualization through similar forms of exile. Her archival traces move us beyond the culture of dissemblance, even if only for a moment, to help us imagine radical possibilities of reinvention in life and death.

Notes:

[1] “Part of Manteuffelstraße to be renamed after American poet Audre Lorde.” Berliner Zeitung, June 16, 2021, https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/en/manteuffelstrasse-to-be-renamed-after-the-us-poet-and-activist-audre-lorde-li.165529?fbclid=IwAR09ngnOJkc8qVoTRf18Y54O1Oebre6eemzUYhNorXDSeG2GFib3bmlON9c

[2] “Activism to promote LBTIQ human rights in Namibia. Online talk with Liz Frank, Windhoek, Namibia.” Blog der Hirschfeld-Eddy-Stiftung. https://blog.lsvd.de/activism-to-promote-lbtiq-human-rights-in-namibia-online-talk-with-liz-frank-windhoek-namibia/

[3] Wright, Michelle. 2015. Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 4, 20.

[4] Smith, William Gardner. “Negroes in Germany Set Styles Until Nazis Started Hate Drive.” The Pittsburgh Courier · Sat, Sep 7, 1946.

[5] Robby Aitken and Eve Rosenhaft, Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diasporic Community, 1884-1960, Cambridge University Press, 2013, 254. My thanks to my collaborator Brigette Reiss for locating the primary documents I have used to reconstruct Madeleine Garber’s life history

[6]Smith, William Gardner. Last of the Conquerors. New York: Farrah, Strauss, 1948.

[7] Polk, Khary Oronde. Contagions of Empire: Scientific Racism, Sexuality, and Black Military Workers Abroad, 1898-1948. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020, 218.

[8] Polk 8.

Khary Oronde Polk is Associate Professor of Black Studies & Sexuality, Women's and Gender Studies at Amherst College. He is the author of Contagions of Empire: Scientific Racism, Sexuality, and Black Military Workers Abroad, 1898-1948 (University of North Carolina Press). Contagions of Empire was a finalist for the Organization of American Historians 2021 Lawrence Levine Prize, awarded to the best book in American cultural history.